Information uncovered by activists in Berkeley, California, revealed a web of cooperation between state, local and federal authorities as they secretly spied on a political rally. This smoking gun conclusively proves that federal agencies actively partner with local law enforcement to facilitate secret dragnet surveillance and indicates this is likely going on across the country.

Specifically, a U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) fusion center partnered with Berkeley police to secretly spy on a 2018 “No To Marxism in Berkeley” rally. Local law enforcement borrowed high tech cameras with facial recognition technology from the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC) and secretly deployed them in Civic Center Park in order to surveil the rally organized by right-wing groups along with expected counterprotests by Antifa. NCRIC is part of the nationwide DHS Fusion Center Enterprise.

After Oakland Privacy uncovered information through open records requests, Berkeley City Manager Dee Ridley-Williams admitted the city borrowed Avigilon hi-tech cameras from NCRIC to conduct surveillance on the rally. According to Oakland Privacy, these IP enabled cameras are equipped with advanced analytics including appearance search recognition and movement detection. An email obtained by the organization revealed that Berkeley police gave officers at the NCRIC log-in credentials for the cameras and therefore access to any footage collected during the protest. Oakland Privacy’s Tracy Rosenberg said, “With NCRIC’s robust facial recognition capacities and close collaboration with the FBI and Joint Terrorism Task Force, all individuals in, at, near or by the park or other parts of downtown Berkeley on August 5, 2018, should assume their identities are known to the Trump Administration and the FBI.”

Activists discovered that the city borrowed cameras from the fusion center quite by accident.

After a rash of gun violence in and near Berkeley’s San Pablo Park in August 2018, city officials asked to install security cameras in the park under an “exigent circumstances” exceptions in the city’s surveillance transparency ordinance. That law requires government agencies to get council approval before obtaining or deploying any surveillance technology. The exigent circumstances exception would have required a review of the technology within 90 days, but the city ultimately installed the cameras under an exception in the law that allows fixed cameras on city property.

The city contracted for the park cameras with Edgewood Integration in January 2019, The Avigilon system is the same setup that was borrowed from the NCRIC.

Fast forward to July 2019. As the Berkeley City Council was considering an ordinance to ban facial recognition technology in the city, a policy recommendation drafted by the city’s Information Security Manager, Tom Ray, suggested that the San Pablo Park cameras be exempted from the facial recognition ban. The document reveals that the CCTV cameras installed in the park use behavioral AI, which includes gait analysis, lip-reading, and voice recognition. The document also indicates that the system could use face pattern recognition. An October 2018 email obtained by Oakland Privacy confirmed that the city intended to use facial recognition with the cameras in San Pablo Park all along.

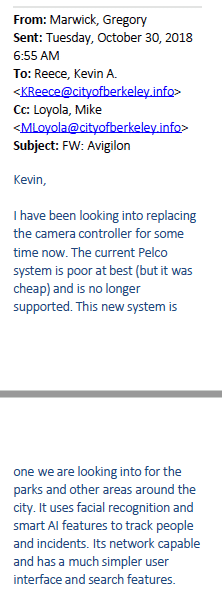

A second email between Berkeley Detective Joseph Le Doux and Jeff Couthren, an equipment tech at NCRIC, tipped Oakland Privacy off to the fact that there was already an Avigilonn system in operation before the cameras were approved for San Pablo Park.

Note that this email is dated Aug 2, 2018. The contract for the park system was not finalized until five months later. This email had to refer to a camera system in place before the acquisition of the San Pablo Park cameras. Oakland Privacy had no knowledge of any such cameras and they were never subjected to the city’s surveillance transparency process.

On Sept. 17, 2019, Oakland Privacy sent a letter to the Berkeley City Council suggesting that both the cameras in San Pablo park and the unknown cameras referred to in the NCRIC email should be put through the transparency process. In response, Berkeley City Councilmember Kate Harrison contacted the Berkeley the city manager, who told her that the cameras used during the August 4, 2018, free speech rally were “borrowed from the NCRIC.”

Rosenberg said the actions of the city violated “pretty much every single word of the surveillance transparency ordinance.” Furthermore, the use of facial recognition cameras to surveil a political gathering is “exactly what abusing the First Amendment looks like.”

The Tenth Amendment Center has long believed that federal, state and local law enforcement cooperate to create a national surveillance network, sharing manpower and equipment, and passing information back and forth through fusion centers and the broader Information Sharing Environment (ISE).

Fusion centers were sold as a tool to combat terrorism, but that is not how they are being used. The ACLU pointed to a bipartisan congressional report to demonstrate the true nature of government fusion centers: “They haven’t contributed anything meaningful to counterterrorism efforts. Instead, they have largely served as police surveillance and information sharing nodes for law enforcement efforts targeting the frequent subjects of police attention: Black and brown people, immigrants, dissidents, and the poor.”

Fusion centers operate within the broader ISE. According to its website, the ISE “provides analysts, operators, and investigators with information needed to enhance national security. These analysts, operators, and investigators…have mission needs to collaborate and share information with each other and with private sector partners and our foreign allies.” In other words, ISE serves as a conduit for the sharing of information gathered without a warrant. Known ISE partners include the Office of Director of National Intelligence which oversees 17 federal agencies and organizations, including the NSA. ISE utilizes these partnerships to collect and share data on the millions of unwitting people they track.

The federal government facilitates this network by providing grant money to local law enforcement agencies for a vast array of surveillance gear, including ALPRs, stingray devices, cameras and drones. The federal government essentially encourages and funds a giant nationwide surveillance net and then taps into the information via fusion centers and the ISE.

The use of facial recognition on the Berkeley surveillance cameras is particularly troubling. The FBI rolled out a nationwide facial-recognition program in the fall of 2014, with the goal of building a giant biometric database with pictures provided by the states and corporate friends.

In 2016, the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law released “The Perpetual Lineup,” a massive report on law enforcement use of facial recognition technology in the U.S. You can read the complete report at perpetuallineup.org. The organization conducted a year-long investigation and collected more than 15,000 pages of documents through more than 100 public records requests. The report paints a disturbing picture of intense cooperation between the federal government, and state and local law enforcement to develop a massive facial recognition database.

“Face recognition is a powerful technology that requires strict oversight. But those controls, by and large, don’t exist today,” report co-author Clare Garvie said. “With only a few exceptions, there are no laws governing police use of the technology, no standards ensuring its accuracy, and no systems checking for bias. It’s a wild west.”

With facial recognition technology, police and other government officials have the capability to track individuals in real-time. These systems allow law enforcement agents to use video cameras and continually scan everybody who walks by. According to the report, several major police departments have expressed an interest in this type of real-time tracking. Documents revealed agencies in at least five major cities, including Los Angeles, either claimed to run real-time face recognition off of street cameras, bought technology with the capability, or expressed written interest in buying it.

As the documents obtained by Oakland Privacy show, the Avigilon system Berkeley police borrowed from the fusion center and later installed in San Pablo park feature this kind of capability. Given the secrecy of the operation, we have to assume facial recognition data was collected during the rally and transmitted to state and federal databases – all without a warrant or probable cause.

This is a smoking gun that proves beyond doubt that our worst fears about the growing national surveillance state are a reality.

- South Carolina Declares “Tariff of Abominations” Null and Void - November 24, 2024

- Tench Coxe: Forgotten Federalist who Helped Influence Ratification of the Constitution - November 18, 2024

- States vs. Feds: The 10th Amendment Battle Over Conscription in the War of 1812 - November 15, 2024