When people think of the causes of the American War for Independence, they think of slogans like “no taxation without representation” or cause célèbre like the Boston Tea Party.

In reality, however, what finally forced the colonials into a shooting war with the British Army in April 1775 was not taxes or even warrant-less searches of homes and their occupation by soldiers, but one of many attempts by the British to disarm Americans as part of an overall gun control program, according to David B. Kopel.

Furthermore, had the American colonies lost their war for independence, the British government intended to strip them of all their guns and place them under the thumb of a permanent standing army.

In his paper titled “How the British Gun Control Program Precipitated the American Revolution,” Kopel claims that various gun control policies by the British following the Boston Tea Party, including a ban on firearm and gunpowder importation, tells us not only the purpose of the Second Amendment, but its relevance within the context of today’s gun control debate.

“The ideology underlying all forms of American resistance to British usurpations and infringements was explicitly premised on the right of self-defense of all inalienable rights,” Kopel writes. “From the self-defense foundation was constructed a political theory in which the people were the masters and government the servant, so that the people have the right to remove a disobedient servant. The philosophy was not novel, but was directly derived from political and legal philosophers such as John Locke, Hugo Grotius, and Edward Coke.”

Kopel writes that two important things underlined the American response to the British policies. One was the practical concept of self-defense, which British disarmament measures was making more difficult. The other, and more relevant concept, was that “Americans made no distinction between self-defense against a lone criminal or against a criminal government.”

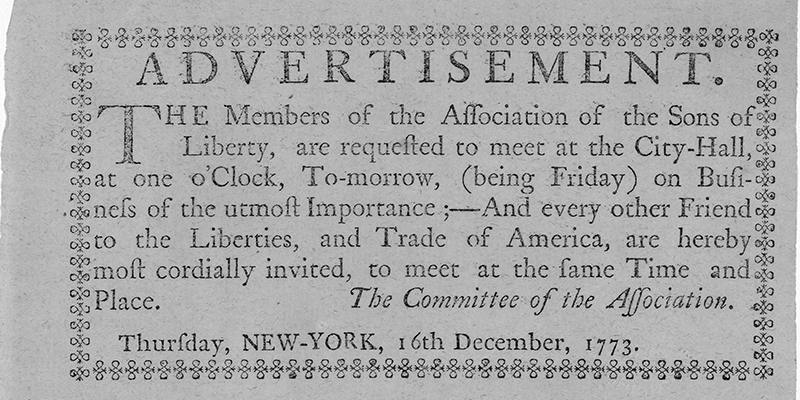

Following the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, in which the Sons of Liberty boarded three ships carrying East India Company cargo and dumped forty-six tons of tea ships of tea to prevent its landing, the British government introduced a series of retaliatory measures known as the Intolerable Acts. Among the actions was the closure of Boston’s port, effectively cutting off all trade.

However, Kopel writes, “it was the possibility that the British might deploy the army to enforce them (the Intolerable Acts) that primed many colonists for armed resistance.”

An example of this is a South Carolina newspaper essay, reprinted in Virginia, that urged that any law that had to be enforced by the military was necessarily illegitimate (bold emphasis added).

“When an Army is sent to enforce Laws, it is always an Evidence that either the Law makers are conscious that they had no clear and indisputable right to make those Laws, or that they are bad [and] oppressive. Wherever the People themselves have had a hand in making Laws, according to the first principles of our Constitution there is no danger of Nonsubmission, Nor can there be need of an Army to enforce them.”

The British Army had already been occupying American cities like Boston since 1768, where the notorious Boston Massacre took place in 1770. Following the passage of the intolerable Acts, the Massachusetts Government Act dissolved the provincial government in the state, and General Thomas Gage was appointed royal governor, all which inflamed tensions and prompted backlash from Americans who saw it as the Crown attempted to force their colonies into submission.

Tensions were so great, in fact, that the shooting might have started much earlier than Lexington and Concord. In one incident, General Gage sent Redcoats to squash an “illegal” town meeting in Salem, only to retreat when, according to one of Gage’s aides, three thousand armed Americans arrived.

It was clear to the British that gun control measures would be necessary if they were to maintain their rule. Gage had only 2,000 troops in Boston, while there were thousands of armed men in Boston and more in the surrounding area.

One solution, Kopel writes, was to deprive the Americans of gunpowder. In September 1774, several hundred Redcoats raided a Charlestown powder house – where militias and merchants stored their gunpowder due to its volatile nature – and seized all but the powder belonging to the colonial government.

“Gage was within his legal rights to seize it,” Kopel concludes. “But the seizure still incensed the public.”

Known as the Powder Alarm, this also nearly started the Revolution when rumors spread wildly that the Redcoats had started shooting. In response, 20,000 militiamen were mobilized that same day and marched on Boston – they later turned around once they learned the truth.

The Powder House (“Magazine”) is near the northern edge of this detail from a 1775 map of the Siege of Boston.

Still, Kopel writes, the message was clear:

“If the British used violence to seize arms or powder, the Americans would treat that seizure as an act of war, and the militia would fight,” he writes. “And that is exactly what happened several months later, on April 19, 1775.”

Following the Powder Alarm, the militia of the towns of Worcester County assembled at the Worcester Common, where the Worcester Convention ordered the resignations of all militia officers who had received their commissions from the royal governor. The officers promptly resigned, and then received new commissions from the Worcester Convention, independent of the British administration.

Governor Gage then tried another approach – warrantless searches of people for arms and ammunition without any provocation. The policy drew fierce criticism from the colonists. In fact, the Boston Gazette wrote that of all General Gage‘s offenses, it was this one that outraged people the most.

In October 1774 the Provincial Congress convened, with John Hancock acting as its president. The Congress adopted a resolution that condemned the military occupation of Boston and called on private citizens to arm themselves and engage in military drills. The Provincial Congress also appointed a Committee of Safety, giving it the power to call up the militia. This meant that the militia of Massachusetts “no longer answered to the British government,” Kopel writes. “It was now the instrument of what was becoming an independent government of Massachusetts.”

Not surprisingly, British officials in England were eager to see outright gun confiscation in order to effectively suppress any resistance to their rule. Lord Dartmouth, the royal Secretary of State for America, articulated this sentiment in a letter to Governor Gage.

“Amongst other things which have occurred on the present occasion as likely to prevent the fatal consequence of having recourse to the sword, that of disarming the Inhabitants of the Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and Rhode Island, has been suggested. Whether such a Measure was ever practicable, or whether it can be attempted in the present state of things you must be the best judge; but it certainly is a Measure of such a nature as ought not to be adopted without almost a certainty of success, and therefore I only throw it out for your consideration.”

Gage warned that the only way to carry it out would be to use violence (bold emphasis added):

“Your Lordship‘s Idea of disarming certain Provinces would doubtless be consistent with Prudence and Safety, but it neither is nor has been practicable without having Recourse to Force, and being Masters of the Country.”

The gun confiscation proposal didn’t remain secret for long, as Gage‘s letter read in the British House of Commons and then publicized in America. Two days after Dartmouth’s letter was sent, King George III ordered the blocked importation of arms and ammunition to America, save those with governments permits. No permit, Kopel writes, was ever granted, and the ban would remain in effect until after the War of Independence ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783.

Having banned the import on all guns and ammunition, the British moved next to seize that which remained in colonial hands. In anticipation of such a seizure at Fort William and Mary in December 1774, four hundred New Hampshire patriots preemptively captured all the material at the fort.

Eventually, Kopel writes “Americans no longer recognized the royal governors as the legitimate commanders-in-chief of the militia. So without formal legal authorization, Americans began to form independent militia, outside the traditional chain of command of the royal governors.”

It was such a militia that assembled at the Lexington Green and the Concord against Gage’s Redcoats in April 1775. Following the battle, the colonials lay siege to Boston. The British response in other colonies was a swift move to confiscate or destroy firearms. In Virginia, they seized twenty barrels of gunpowder from the public magazine in Williamsburg and removed the firing mechanisms in the guns, making them impossible to shoot.

Meanwhile, in Boston, General Gage carried out his own gun confiscation policy against the remaining Bostonians, but having learned his lesson from Lexington and Concord, he tried a more furtive approach by offering them the opportunity to leave town if they gave up their arms. Within days, Kopel writes, 2,674 guns were handed over to the British. Gage then promptly turned back on his promise and initially refused to allow anyone to leave. Only food shortages led him to permit more emigration from the city.

Although there is room for speculation as to what would have happened had the American colonies lost the War of Independence, historical documents make some things very clear. When a British victory seemed likely in 1777, Colonial Undersecretary William Knox drafted a plan titled “What Is Fit to Be Done with America?” Intended to prevent any further rebellions in America, the plan called on the establishment of the Church of England in all the colonies, along with a hereditary aristocracy.

But the most ominous measure it would have enacted would have been a permanent standing army, along with the following (emphasis added):

The Militia Laws should be repealed and none suffered to be re-enacted, [and] the Arms of all the People should be taken away . . . nor should any Foundery or manufactuary of Arms, Gunpowder, or Warlike Stores, be ever suffered in America, nor should any Gunpowder, Lead, Arms or Ordnance be imported into it without Licence . . .”

Many gun control policies in America today follow the British blueprint. The federal Gun Control Act of 1968, for example, prohibits the import of any firearm which is not deemed suitable for “sporting” purposes by federal regulators. Certain cities openly declare their gun fees are intended not to prevent the wrong people from owning guns, but to discourage all private citizens from owning them.

“To the Americans of the Revolution and the Founding Era,” Kopel writes, “the late twentieth century claim that the Second Amendment is a collective right and not an individual right might have seemed incomprehensible. The Americans owned guns individually, in their homes. They owned guns collectively, in their town armories and powder houses. They would not allow the British to confiscate their individual arms, or their collective arms; and when the British tried to do both, the Revolution began.”

Yet, Kopel believes “the most important lesson for today from the Revolution is about militaristic or violent search and seizure in the name of disarmament,” something that occurred in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Local law enforcement confiscated firearms, many times at gunpoint. A federal district judge properly issued an order finding the gun confiscation to be illegal.

“Gun ownership simpliciter ought never be a pretext for government violence,” Kopel concludes. “The Americans in 1775 fought a war because the king did not agree. Americans of the twenty-first century should not squander the heritage of constitutional liberty bequeathed by the Patriots.”

It is easy to see, then, why modern gun control advocates are the spiritual successors of the British government our forefathers opposed, for while gun grabbers call for restrictions on the right of private citizens to keep and bear arms, they are all but silent on the dangers of having standing army in America or the blatant militarization of police departments.

Their reason for disarming American citizens today is the same as that of the British in the 1770s.

- Limited or Absolute Power: Warnings from Anti-Federalist Agrippa - April 17, 2024

- Mercy Otis Warren: Constitution Would “Terminate in the Most Uncontrolled Despotism” - February 24, 2024

- Deciphering the Commander-in-Chief Clause - February 9, 2024