The standard version of the whiskey rebellion story, the one which I believed until I started reading on the topic, goes something like this…. In 1791, the Congress passed a whiskey tax. In 1792, four back-woods counties in western Pennsylvania, unable to cooperate and accept the new reality that they were subservient to federal authority, resisted the tax and initiated a violent response which had to be put down by the federal government. So, in 1794, President Washington dispatched 13,000 troops, put down the resistance then arrested (and pardoned) the ring-leaders. With the rebellion quashed, federal supremacy lived happily ever after.

It only takes a few minutes of web surfing, however, to discover that this story line has some factual problems.

Not Just Pennsylvania

One problem we encounter with the official story line is that the whiskey rebellion was actually not limited to Pennsylvania. It was a wide-spread resistance effort. The National Park Service says,

“The Whiskey Rebellion took place throughout the western frontier. There was not one state south of New York whose western counties did not protest the new excise with some sort of violence.”

And Murray Rothbard writes,

“President Washington and Secretary Hamilton chose to make a fuss about Western Pennsylvania precisely because in that region there was a cadre of wealthy officials who were willing to collect taxes. Such a cadre did not even exist in the other areas of the American frontier; there was no fuss or violence against tax collectors in Kentucky and the rest of the back-country because there was no one willing to be a tax collector.”

In short, it seems that President Washington made an example of western Pennsylvania because the rest of the western frontier had successfully nullified the whiskey tax.

Tax Repealed

Another problem with the standard whiskey tax story comes when we learn that the tax was repealed only 11 years after its inception. On this point, Rothbard writes,

Rather than the whiskey tax rebellion being localized and swiftly put down, the true story turns out to be very different. The entire American back-country was gripped by a non-violent, civil disobedient refusal to pay the hated tax on whiskey. No local juries could be found to convict tax delinquents. The Whiskey Rebellion was actually widespread and successful, for it eventually forced the federal government to repeal the excise tax.

Even wikipedia, no bastion of classical liberal thought, says,

The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that the new national government had the willingness and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws. The whiskey excise remained difficult to collect, however. The events contributed to the formation of political parties in the United States, a process already underway. The whiskey tax was repealed after Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party, which opposed Hamilton’s Federalist Party, came to power in 1800. (my emphasis)

Repeal Overseen by a Whiskey Rebel

Another possible problem with the standard story, or at least an interesting aspect of the story, comes in the form of a man named Albert Gallatin. In 1794, Gallatin’s name appeared on a list of whiskey rebels. The National Park Service tells us,

Another possible problem with the standard story, or at least an interesting aspect of the story, comes in the form of a man named Albert Gallatin. In 1794, Gallatin’s name appeared on a list of whiskey rebels. The National Park Service tells us,

Unfortunately for Gallatin, the government officials did not differentiate between the moderates and the radicals who took part in these meetings. Participation brought guilt as far as those in the government were concerned. In 1794 the militia called by Washington marched to dispel the rebels in western Pennsylvania. They also brought a list of names of participants that certain members of the Presidential staff wanted arrested. This list included Brackenridge and Gallatin.

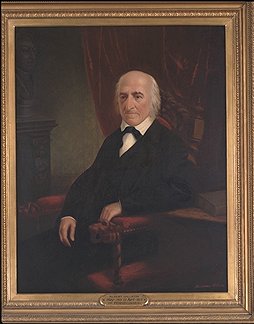

Is it coincidental that Gallatin, accused of being a whiskey rebel, was the man who became Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury in 1801 and oversaw the 1802 repeal of the whiskey tax? According to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau,

Elected to Congress after the rebellion, Gallatin worked for a more exact accounting of the Federal government’s finances, leading President Thomas Jefferson to appoint him Secretary of the Treasury, a post he also held under President James Madison. In 1802, Gallatin oversaw the ending of all direct, internal Federal taxes, including the distilled spirits tax.

Conclusion

It appears that the whiskey tax was a Constitutional tax, and I don’t advocate civil disobedience against laws which are Constitutional and just. However, the whiskey rebellion still offers a tactical lesson for us when confronted with an unconstitutional or unjust law. It confirms the lesson that we have learned from other events such as the Civil Rights movement, India’s fight for Independence from Great Britain, and the Underground Railroad. When confronted with an unjust or unconstitutional law, civil disobedience can be an effective counter-tactic.

In the case of the whiskey rebellion, civil disobedience was effectively combined with jury nullification and with a refusal to enforce by officials in several states. These activities made the tax ineffective while it was in force and impacted the 1800 elections in a way that led to the repeal of the unpopular tax.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is excerpted from an article originally published Mar. 21, 2010.

- The Whiskey Rebellion: True History and Hidden Lessons - February 24, 2015

- Prohibition Repeal: Another Nullification Success Story - December 4, 2014

- Why American Businesses Should Understand Nullification - December 11, 2013