The Supreme Court’s Citizens United Corporate Campaign case Should Be Controversial. But Not for the Reason You Think

The Supreme Court’s Citizens United Corporate Campaign case Should Be Controversial. But Not for the Reason You Think

If you have any doubt about the ability of the political Left to set the agenda in this country, look at the controversy over the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United corporate campaign finance case.

What most people have heard about the case is that it “allowed corporations to spend unlimited amounts in federal elections,” a ruling the extreme left considers controversial. (The Court voided a section of federal campaign law.) But we rarely hear that the Court upheld only the rights of corporations to spend independentlyof the candidates—and that the justices left in place the part of federal law that bans corporations from donating to candidates.

And we never hear that, over the dissent of Justice Thomas, Citizens United upheld federal requirements that corporate campaign expenditures be publicly disclosed. The Left does not consider that part of the decision to be controversial.

Yet from an objective constitutional point of view, the Court’s decision protecting corporate First Amendment rights is far more defensible than its decision upholding the disclosure requirements.

First, it is dubious whether the Constitution even gives Congress power to regulate the source and amount of campaign contributions and expenditures. The background and meaning of the Constitution’s “Time, Place and Manner Clause”—which Congress uses to justify such laws—strongly suggests not.

Second, the position of the more extreme leftists—that corporate speech is not protected by the First Amendment—is absurd to anyone who has studied the evidence. The position is inconsistent with the plain language of the First Amendment, which does not discriminate according to who is speaking. It is inconsistent with the Founders’ understanding of the terms “freedom of speech” and “freedom of the press.” It is factually inconsistent with the guarantee of a free press, because, of course, most newspapers and broadcast stations are incorporated. And it is inconsistent with decisions of the Court itself—particularly those written by “progressive” justices—that have upheld the First Amendment rights of corporations such as the New York Times and the NAACP.

Third, the position that “freedom of speech” is severable from spending money getting out your message is similarly absurd: Every communication except, perhaps screaming on the street corner, requires expenditure to be effective. Microphones have to be purchased. Writers have to be employed. Advertising space and time has to be bought. And so on.

We spend public time discussing such ridiculous arguments only because the Left is able to put them on the public agenda.

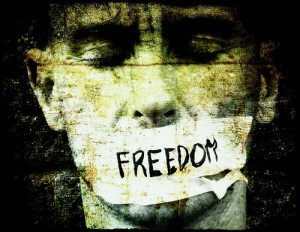

We would do far better talking about the other part of the Citizens United opinion—the part concluding that anonymous speech is not protected by the First Amendment. That is the much more questionable part of the decision.

Anonymous and pseudonymous expression was part of what the founding generation meant by “freedom of speech” and “freedom of the press.” Anonymous and pseudonymous essays were central to the debate over the Constitution itself. The Federalist Papers, the most famous product of those debates, were written under a pen name. So were most of the other important articles and pamphlets arguing for or against the Constitution.

There were, and are, a several good reasons why people wish to make their arguments without their names being known.

* They may wish their arguments to be considered on their merits without being dismissed because of who wrote them. During the Founding Era, this was commonly given as a reason for anonymity. It is a particularly important consideration today, when publicists have become experts at destroying the credibility of perfectly good arguments by vilifying their authors.

* Writers may fear retribution from unscrupulous and powerful persons and interest groups. This, also, is a very modern concern.

* Writers may wish to participate marginally in politics without letting it consume their lives. Anyone who has been flooded with phone calls from reporters knows how disruptive that can be. Forcing people to disclose their names discourages all from participating who do not wish to become public figures.

What if an anonymous author abuses the First Amendment by hiding behind his anonymity to slander others? The Founding Generation had a good answer to that: the law of defamation. If the plaintiff had a decent case, he could sue the publisher of the article, and force the publisher to disclose the writer.

But occasional instances of abuse do not justify disclosure of those who are innocent of abuse.

In a fairer world, Citizens United would be a controversial case. But not because of the no-brainer ruling that people don’t give up their First Amendment rights when they incorporate. What would be controversial would be the Court’s refusal to protect the First Amendment right to contribute to the public debate without having one’s life destroyed.

One more point: Highlighting the corporate contribution part of the decision while ignoring the rest serves the purpose of inaccurately portraying the Court as “conservative.” But that’s a topic for another time.

- The Truth about the Much-Abused Commerce Clause - February 28, 2024

- The Meaning of “Regulate Commerce” to the Constitution’s Ratifiers: An Update - February 7, 2024

- Why It May be Impossible to Disqualify Trump from the Presidency - January 8, 2024