In the 1850s, a banging on a door marked the beginning of a seven-year saga that would end with a state defying the U.S. Supreme Court. That defiance continues to this day.

In the 1850s, a banging on a door marked the beginning of a seven-year saga that would end with a state defying the U.S. Supreme Court. That defiance continues to this day.

Joshua Glover was playing cards in his single-room, dirt-floor cabin near the shore of Lake Michigan when he heard the ruckus outside. He yelled at his companions not to open the door when the insistent banging started, but it was too late. The door was flung open and three men charged into the room. One was armed with a gun. Glover resisted, but a second man cracked him over the head with a pair of cuffs, and Glover fell to his dirt floor, bleeding profusely. The men drug him out of his home, threw him roughly into a wagon and spirited him away toward Milwaukee.

Under federal law, this kidnapping was perfectly legal.

The three men who rushed into Glover’s home that night were Deputy U.S. Marshal Charles C. Cotton, a deputy marshal by the last name Kearney and Bennami Stone Garland. Garland had in his possession an arrest warrant signed by federal judge Andrew G. Miller based on his ownership of Glover.

Joshua was a fugitive slave.

Several years earlier, he ran away from Garland’s farm near St. Louis. Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Garland had the absolute right to travel north and reclaim his “property.” Joshua didn’t even have the right to testify on his own behalf or present evidence to a court of law. The word of the “master” was sufficient to justify kidnapping under federal law. Anybody interfering was subject to arrest and prosecution.

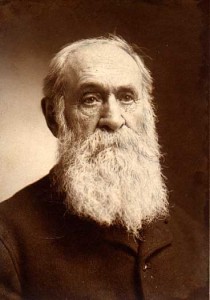

Many northerners refused to accept the federal edict. Among the defiant in Milwaukee was a newspaper editor by the name of Sherman Booth. He was a staunch abolitionist, and when he got word marshals had captured an accused fugitive in nearby Racine and locked him up in the Milwaukee jail, he sprang into action.

After investigating the matter and printing a handbill that asked the question, “shall a man be dragged back to Slavery from our Free Soil, without an open trial of his right to Liberty?”

Later, Booth rode through town crying out, “Free citizens, who do not wish to be made slaves or slave-catchers, meet at courthouse square at 2 o’clock.”

By 2:30 between 3,000 and 5,000 people gathered in front of the courthouse building, also the site of the city jail.

The crowd was far from a disorganized mob. In fact, the gathered masses elected representatives from each city ward and drafted resolutions. The gathering was essentially an impromptu political meeting. But the demands for Glover’s release fell on deaf ears. Many Milwaukeeans delivered, fiery speeches, including Booth. Ultimately, the crowd took matters into its own hands and broke Joshua out of the jail. Supporters rushed him away and took him to a safe house on the Underground Railroad. After a three week journey, Joshua stowed away on a steamer and found freedom in Canada.

Booth helped Joshua Glover win his freedom. He would spend the next seven years fighting for his own.

The feds arrested him and charged him with aiding a fugitive slave. Booth was released on bail, but two months later, he intentionally surrendered to federal marshals in order to bring the case before the court. A day after the surrender, Booth’s attorney, Byron Paine, applied to Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Abram D. Smith for a writ of habeas corpus.

Paine used Thomas Jefferson’s reasoning from the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, arguing that the state has a sovereign right to assert its authority when the federal government violates the Constitution. He held that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was unconstitutional because it denied due process and vested judicial authority in court commissioners.

Smith agreed, ruled the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional and ordered Booth released.

The federal government appealed the decision to the full Wisconsin Supreme Court, holding that the state court had no authority to release a federal prisoner and that it was the duty of federal judges to determine the constitutionality of a federal act. Lawyers for the federal government also insisted that the Fugitive Slave Act was constitutional. On July 19, 1854, the Wisconsin Supreme Court unanimously upheld Smith’s decision to release Booth. Chief Justice Edward V. Whiton and Smith declared the 1850 law unconstitutional. Justice Samuel Crawford wrote a concurrent opinion finding Booth’s writ of commitment to be invalid but the Fugitive Slave Act constitutional.

A short time later, a federal grand jury indicted Booth. This time, the Wisconsin Supreme Court refused to issue a writ of habeas corpus, asserting that since the case was under federal jurisdiction, it could not intercede until after it was tried.

A jury found Booth guilty, sentenced him to one month in jail and fined him $1,000. After his conviction, the Wisconsin Supreme Court issued a writ of habeas corpus and ordered Booth released again, after concluding it could consider the jurisdictional issue.

When U.S. Attorney General Kaleb Kushing appealed the Wisconsin Supreme Court rulings to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Wisconsin justices refused to send a response, delaying the case for nearly two years. An historical document published by the Wisconsin courts described the effect of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s refusal to comply.

The Court’s action in refusing to make a return to the writ of error issued by the U.S. Supreme Court was tantamount to judicial nullification of part of the 1789 federal act which by that time had served as the basis for federal review of almost 200 cases.

When the Supreme Court finally heard the case, it unanimously overturned the Wisconsin Decisions. Chief Justice Roger Taney (of Dred Scott fame) affirmed the constitutionality of the U.S. Supreme Court’s appellate authority and declared the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 constitutional.

A short time later, the Wisconsin legislature passed a series of resolutions condemning the U.S. Supreme Court decision.

We regard the action of the Supreme Court of the United States, in assuming jurisdiction in the case before mentioned, as an arbitrary act of power, unauthorized by the Constitution, and virtually superseding the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus and prostrating the rights and liberties of the people at the foot of unlimited power.

Resolved, That this assumption of jurisdiction by the federal judiciary, in the said case, and without process, is an act of undelegated power, and therefore without authority, void, and of no force.

Only a month after the Supreme Court handed down its decision, Byron Paine was elected to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The election of Booth’s lawyer to the state’s highest court was viewed as public affirmation of his states’ rights position. And as the Wisconsin court’s paper put it “approval by the state electorate of the idea that the state could and should nullify and defy a law of the United States.”

When the Wisconsin Supreme Court received the request to file the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling reversing the state court’s decisions and dismissals in the Booth case, it refused. To this day, those mandates have not been filed, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision has never been officially recognize by the state of Wisconsin.

Federal authorities took Booth back into custody in March of 1860. He remained in prison even after serving his one-month sentence because he refused to pay the fines. In August 1860, armed men broke Booth out of the federal custom house in Milwaukee. Booth spent several months speaking at public events until he was recaptured. He remained imprisoned until Pres. Buchanan pardoned him on the last day of his presidency.

Wisconsin’s battle with the federal government destroys many myths surrounding nullification – chief among them that it was the domain of slavers and racists. It also serves to illustrate the power of state resistance. Wisconsin’s refusal to bow down to federal power offers a bold blueprint for states today to follow.

Some might declare Wisconsin’s stand a failure. After all, Booth ultimately served his time in federal prison. But that would be like declaring Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on that Montgomery bus a failure because she was arrested, jailed and fined. Placed in a larger context, Rosa’s stand was a significant strategic victory. So, while Wisconsin’s defiance may seem insignificant in isolation, it was part of a larger battle against the Fugitive Slave Act fought in nearly every northern state – a battle that was extremely effective in thwarting enforcement of that draconian law.

And the final chapter on nullification has yet to be written. Perhaps someday, historians will look back at Joshua Glover, Sherman Booth, Byron Paine and other actors during that tumultuous time in the same way they view Parks today, and praise them as trailblazers who hacked out a path that was followed by those yearning for freedom in the 21st century.

- Writs, Riots, and Redcoats: Hancock’s Spark of the Revolution - January 17, 2026

- The National Bank That Breached the Articles of Confederation - June 2, 2025

- Virginia Association of 1769: A Step Toward Continental Unity - May 12, 2025