I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America…one nation…indivisible.

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America…one nation…indivisible.

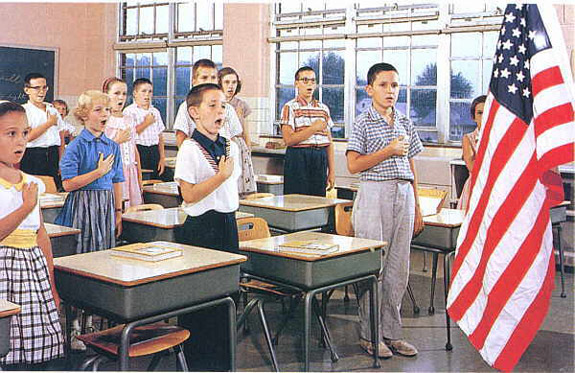

If you attended school, you know the pledge by rote. You parroted those words thousands of times without even really thinking about what they mean.

But does mere repetition make something true?

We take the words of the pledge for granted, as if they represent some unassailable truism. We don’t have to prove the founders crated “one nation.” We don’t need to debate the term “indivisible.” It just IS, because, well, it IS.

Dangerous – this blind acceptance of mantra, this unchallenged expression of orthodoxy. In the words of George Orwell, “Orthodoxy means not thinking – not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness.”

The idea that “one American people” created a Constitution forming “one nation” under one supreme federal government serves as the foundation for every expansion of federal power today. If this indeed defines the structure of America, it removes virtually all authority from the states. They possess no sovereign power of their own, and may only exercise authority with the benevolent blessing of the general government. The feds get the bread; states scavenge for crumbs, ultimately left to beg for sustenance. This clearly describes the system of governance in the U.S. today.

But this nearly universally accepted version of America bears absolutely no resemblance to the vision cast by those who created the United States. They believed that the people of the sovereign states were delegating specific powers to a federal government for their mutual benefit. But they refused to relinquish the sovereignty of their individual states, and they never gave in to those who favored creating a “national” government.

By and large, the American people of the founding era feared centralized power. They fought a bloody revolution to free themselves from a King they considered tyrannical. As a result, they created a federal government with limited powers, and included checks and balances between the departments. But they also assumed the states retained all powers not delegated and would serve as a check on federal power.

During the Massachusetts ratifying convention, delegate Fisher Aims argued for the inclusion of what would later become the Tenth Amendment.

“A consolidation of the States would subvert the new Constitution, and against which this article is our best security. Too much provision cannot be made against consolidation. The State Governments represent the wishes and feelings, and the local interests of the people. They are the safeguard and ornament of the Constitution; they will protect the period of our liberties; they will afford a shelter against the abuse of power, and will be the natural avengers of our violated rights.”

Indeed, the Massachusetts ratifying convention included a call for amendments in its ratifying document.

That it be explicitly declared that all powers not expressly delegated by the aforesaid Constitution are reserved to the several states, to be by them exercised.

Ultimately, the states ratified the Tenth Amendment, making this concept explicit.

In 1833, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story published Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. The three volume tome became the gold-standard for understanding the U.S. Constitution. Story was an ardent member of the Federalist Party and favored expansive federal power. In order to achieve this, it was imperative that he smash the “compact theory,” which holds that the sovereign states make up the parties to a compact – the Constitution – and retain all powers not delegated. Story based his arguments for expansive and supreme federal authority on the assumption that “one people of America” acting as a whole created the United States, and as a result, the Constitution formed “one nation,” not merely a federation of sovereign states delegating limited powers to the general government.

In 1833, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story published Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. The three volume tome became the gold-standard for understanding the U.S. Constitution. Story was an ardent member of the Federalist Party and favored expansive federal power. In order to achieve this, it was imperative that he smash the “compact theory,” which holds that the sovereign states make up the parties to a compact – the Constitution – and retain all powers not delegated. Story based his arguments for expansive and supreme federal authority on the assumption that “one people of America” acting as a whole created the United States, and as a result, the Constitution formed “one nation,” not merely a federation of sovereign states delegating limited powers to the general government.

Judge Able P. Ushur, a Virginia politician and jurist who also served as U.S. Secretary of State and War, wrote a response aimed at refuting Story’s “one people, one nation” assumption, proving that it was indeed the people acting through their sovereign states that created a federated system.

Many of the powers which have been claimed for the Federal Government, by the political party to which he (Story) belongs, depend upon a denial of that separate existence, and separate sovereignty and independence, which the opposing party has uniformly claimed for the States. It is therefore highly important to the correct settlement of this controversy, that we should ascertain the precise political condition of the several colonies prior to the Revolution.

He goes on to write:

The great effort of Judge Story, throughout the entire work, is to establish the doctrine that the Constitution of the United States is a government of “the people of the United States,” as contradistinguished from the people of the several States; or, in other words, that it is a consolidated and not a federative system. His construction of every contested federal power depends mainly upon this distinction; and hence the necessity of establishing oneness among the people of the several colonies, prior to the Revolution.

Upshur then proceeds to obliterate Story’s argument.

True, the people always remain sovereign in any legitimate political system. But the people of the colonies had already delegated powers to state governments, granting them authority within their borders.

The Virginia lawyer starts by showing that the 13 colonies stood as separate, independent political societies, never united as “one people.” True, they shared an allegiance to the Crown and were all British Citizens, but so were Canadians, and residents of British holdings in India and the Caribbean. In that sense, all British subjects counted as “one people.” But Upshur points out that each colonial government remained sovereign within its own borders and possessed no authority over its neighbor. They were in fact distinct political societies.

These colonial governments were clothed with the sovereign power of making laws, and of enforcing obedience to them, from their own people. The people of one colony owed no allegiance to the government of any other colony, and were not bound by its laws.

They were separate and distinct in their creation; separate and distinct in the changes and modifications of their governments, which were made from time to time; separate and distinct in political functions, in political rights, and in political duties.

Upshur then challenges his readers with a question: when did the people of the states ever give up their distinct sovereignty?

In fact, they never did.

They voted on and declared independence from England as individual states, operating through a Continental Congress created by the states, with representatives chosen by those states. Would a colony not signing on to the Declaration of Independence have been obligated to go to war with Great Britain? Clearly not.

When the colonies formalized their union, the Articles of Confederation expressly maintained state sovereignty.

Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.

And during the war, each state was a party to a treaty made with France.

At the end of the Revolutionary War, King George III ultimately recognized the Colonies’ independence as 13 sovereign states, naming each one individually in the Treaty of Paris.

And finally, the Constitution itself was ratified through state conventions, by delegates elected by the people of each individual state. A state was not bound to the Constitution until it ratified. Rhode Island was the last of the original colonies to approve the Constitution, and it did not send representatives to Congress until after ratification. Clearly, by that point a vast majority of the American population was represented by ratifying states, yet that fact did not bind the people of Rhode Island to the Union. An act representing the majority of Americans did not operate on the small minority of Rhode Islanders, as would be the case if the Constitution was the act of “one American people.”

Madison explained the nature of the federal government in the Federalist 39.

Each State, in ratifying the Constitution, is considered as a sovereign body, independent of all others, and only to be bound by its own voluntary act. In this relation, then, the new Constitution will, if established, be a FEDERAL, and not a NATIONAL constitution.

At no point did the people of the states assemble themselves into “one people.” Proponents of this position can point to no act, to no moment in time when the people recalled all of the powers previously delegated to their state governments and vested them in a national government. Records of the ratifying conventions make this clear. The delegates believed they were approving a Constitution delegating only specific, enumerated powers, not creating an overriding national government. The In fact, many of the state ratifying instruments expressly made this point.

That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness; that every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the government thereof, remains to the people of the several states, or to their respective state governments, to whom they may have granted the same; and that those clauses in the said Constitution, which declare that Congress shall not have or exercise certain powers, do not imply that Congress is entitled to any powers not given by the said Constitution; but such clauses are to be construed either as exceptions to certain specified powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution. – New York ratifying document.

The Constitution delegates authority to a general government for the benefit of the whole. Federal law stands supreme ONLY in pursuance of the Constitution, and all power not given remains with the states and the people. The states stood as sovereign entities before ratification, and they remained sovereign entities after. The people of each state always maintain the right to “resume the powers delegated” if they want to – Lincoln’s cannons not-withstanding.

But why does all of this really matter?

Because separation of power protects our basic liberties. It guards our freedom. And it checks human nature, which often leads those holding power to tyrannize us “for our own good.”

Do we really want to grant the federal government a power monopoly? Authority vested in too few people or institutions poses grave risks to individuals – each one of us. We all understand this intuitively when discussing economic monopoly. We fear the power of marketplace domination by a single company. How quickly we throw caution aside when it comes to government monopoly power.

Upshur understood the danger and viewed the power retained by the states as the only check on the federal government.

Power and patronage cannot easily be so limited and defined, as to rob them of their corrupting influences over the public mind. It is truly and wisely remarked in the Federalist that, “a power over a man’s subsistence is a power over his will.” As little as possible of this power should be entrusted to the federal government, and even that little should be watched by a power authorized and competent to arrest its abuses. That power can be found only in the States. In this consists the great superiority of the federative system over every other. In that system, the federal government is responsible, not directly to the people en masse, but to the people in their character of distinct political corporations. However easy it may be to steal power from the people, governments do not so readily yield to one another.

We’ve wandered down the pathway of consolidation for far too long. “One nation…indivisible” makes for a catchy pledge. But like the beautifully brilliant billowing tentacles of a jellyfish, the words conceal a deadly poison. And now, we the people suffer the consequences of unrestrained, unchecked federal power: the sting of endless wars, unsustainable spending, unimaginable debt, groping and peeking at the airport; control over the foods you eat, the medicines you choose and the amount of water in your toilet; erosion of due process and property rights – the list goes on and on.

We cannot depend on Washington D.C. to limit itself. We cannot trust in the moral clarity and good judgment of federal officials to exercise power “properly.” We must follow the admonition of Thomas Jefferson.

“In questions of power…let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.”

We must let go of the false orthodoxy of the Pledge of Allegiance and rediscover the Republic for which the flag stands.