Uncle Sam ran the biggest budget deficit in seven years in fiscal 2019, according to the Treasury Department.

The $984 billion deficit amounts to 4.7 percent of GDP. That’s the highest percentage since 2012. It was the fourth consecutive year in which the deficit increased as a percentage of GDP. The debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to have increased a hefty 26 percent over last year.

The pundits in the mainstream media tend to focus on the Trump tax cuts as the cause for the surging deficits, but revenues rose in FY2019. Spending is the real culprit. The Trump administration blew through $4.45 trillion. There were significant increases in both military and domestic spending.

But like most things the government does, the reality of government spending remains partially hidden. If you factor in the amount of money the Treasury Department had to spend to pay off public debt, the total outlay for 2019 came in nearly $16 trillion.

When the federal government runs a deficit (expenditures exceed revenues), it must borrow money from the public to cover the spending gap. It does this by issuing Treasury bonds with maturities that range from three to 30 years. Uncle Sam not only has to pay interest on these bonds (totaling $376 billion in 2019 alone); it also has to pay the face value of the bonds when they reach full term. If the government is already running a deficit, it must borrow more money to pay off the bonds as they mature.

During the last fiscal year, the Treasury Department spent nearly 11 trillion redeeming maturing public debt. When you add that to the reported spending of nearly $4.5 trillion, you get a staggering $15.5 trillion in actual federal outlays.

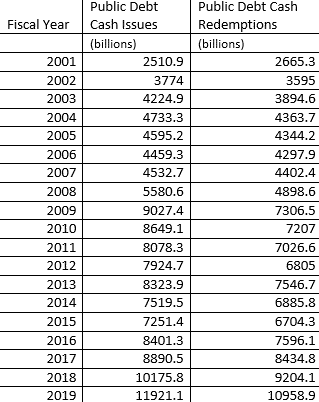

As you can see from the chart, over the last 19 years, public debt cash Issues (total borrowing) increased by 375 percent while public debt cash redemptions (debt payments) increased 311 percent. You can also see that the Trump administration has significantly ratcheted up the borrowing, exceding levels we saw during the Obama years and the Great Recession.

When we talk about spending and debt, most people tend to shrug. After all, the debt has grown precipitously for decades and nothing bad has happened. Even those in the political class who express concern about the debt tend to frame it as a problem that will manifest itself in a few decades. But this kind of spending simply isn’t sustainable. You can kick the can down the road for a long time, but eventually, you run out of road.

And we may run out of road sooner than people think.

Two things could happen that would make the massive debt an immediate problem.

First, interest rates could rise. The Federal Reserve has held rates artificially low for over a decade. Last year, the central bank moved to “normalize” rates. It managed to push the interest rate to 2.5 percent before the stock market tanked. When that happened, the Fed initially put rate hikes on pause and then cut rates three times this year. As economist Mark Brandly explained in an article on the Mises Wire, if rates returned to anywhere near normal, interest payments on the debt could exceed outlays for social security. And with the coming budget deficits, it’s possible that interest payments could surpass a trillion dollars annually in the next decade.

If inflation begins to rear its ugly head, the Fed will find itself between a rock and a hard place. It will either have to increase interest rates and topple the federal government’s budgetary house of cards or keep printing money and collapse the dollar.

The second problem the U.S. Treasury faces is at some point, people will simply quit buying the bonds and financing the ever-increasing debt. Brandly said the current levels of borrowing simply aren’t sustainable.

“The danger here is that lenders at some point may not be willing to loan our government these trillions of dollars a year. In the last 18 years, Public Debt Cash Issues increased at an average rate of almost 9 percent per year. This is not sustainable. If the federal government continues to increase its borrowing at 9 percent annually, in 2030, the feds will need to borrow over $28 trillion to cover their spending on the deficit and debt payments. The moment lenders become unwilling to fund this budget recklessness, the government’s financial houses of cards will collapse.”

When the house of cards does fall down, it will crash the entire U.S. financial system.

The bottom line is that the spending and debt don’t matter — until they do.

- 1761: When American Independence was Born - February 13, 2026

- Writs, Riots, and Redcoats: Hancock’s Spark of the Revolution - January 17, 2026

- The National Bank That Breached the Articles of Confederation - June 2, 2025