EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an excerpt from the book, Conceived in Liberty – Murray Rothbard’s a full treatment of the Colonial period of American history, a period lost to students today.

CHAPTER 31: Ignoring the Stamp Tax

Immobilizing the distribution of stamps, supplemented by official protests to Britain, could only be the first step in the peoples’ nullification of the Stamp Act. For once the act went into effect in November 1765, the colonists, devoid of stamped paper, faced a critical choice: either to carry on normal transactions as if the Stamp Act did not exist, or to stop all business so as not to violate the law.

The latter, the conservative path, avoided any breaking of the law, but would have meant a suicidal stoppage of trade and of the courts that would have quickly brought the colonists to their knees. Many of the royal governors, gravely underestimating the fighting qualities of the resistance movement, confidently expected the latter result. They could not dream that the colonists would make open defiance of the Stamp Act a continuing way of life.

Thus, as the enforcement date drew near, Governor Bernard smugly expected that famine would soon bring Massachusetts to a standstill. Jared Ingersoll calmly predicted that “the distresses which the want of the stampt papers will occasion will put the people… to desire… to introduce and distribute them.” But having disposed of the stamp masters, the colonists were in no mood to submit meekly to economic suicide rather than defy the hated stamp tax.

For the work of nullifying the Stamp Act, ordinary business transactions within the colonies presented no problem. Contracts and exchanges could be made with the simple refusal of bothering about the Stamp Act’s existence. The major problem in domestic business was faced by the newspapers, who were in an exposed position. As November approached, the press reluctantly prepared to close up in obedience to the stamp law, but their courage was buoyed by threats, especially in New York and Boston, to the person and property of the printers should they dare thus surrender to the law. The pattern of press courage was set on November 1, with the bold appearance of the New London Gazette and the Connecticut Gazette without stamps. The great radical organs of liberty, the Boston Gazette and the New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, swiftly followed suit. John Holt, editor of the New York paper, emblazoned on his newspaper the motto “LIBERTY, PROPERTY AND no STAMPS,” which was soon picked up by other leading papers. Other northern newspapers continued to publish, first hedging with such partial disguises as changing their titles or leaving out the printers’ names, but soon they resumed publication full blast.

Burning of the Stamp Act

Only in the South did the bulk of the press display cowardice by suspending operations rather than publishing unstamped. In some cases, courage returned and printing resumed: for example, the (Annapolis) Maryland Gazette and the (Williamsburg) Virginia Gazette. However, the publisher of the latter paper was not trusted by the liberals, who induced another printer to establish a rival Virginia Gazette, which corralled the coveted public printing contract from the House of Burgesses. Neither Charleston paper could be induced to reopen, so that the radicals of that city inaugurated a new unstamped newspaper there. In Wilmington, North Carolina, the radicals turned to violent methods of persuasion—a mob forced the publisher of the North Carolina Gazette to resume publication unstamped, “at the hazard of life, being maimed, or have his printing-office destroyed.” The publisher, however, found himself whipsawed between two masters, the governor and Council finally removing him as public printer for “inflammatory expressions.” The only southern paper that defied the Stamp Act from the start was the Georgia Gazette, which, however, was closed by pressure from the royal governor in late November.

Internal transactions and even the press thus successfully defied the stamp law. The real problem for the colonists was transactions necessarily involving government agencies, which could not easily sanction the continuance of illegal activities. The most vital question was foreign trade, on which many economic activities, especially in the port towns, depended absolutely. For merchants needed clearances from the royal customs officials to ship out of port; without such clearance they were liable to seizure on the high seas by the British navy, which did not have to worry about colonial opposition or rebellious activity on the Atlantic. Domestic transactions requiring government stamps presented a much lighter problem. Marriages, wills, and diplomas could be and were informally recorded, and criminal court procedures did not require stamped paper. Furthermore, a positive advantage accrued to the colonists: the closing of the hated admiralty courts, which were not supposed to function without stamps. Only the civil courts posed a problem for the colonies.

On the crucial question of foreign trade, which could make or break the resistance movement, the colonists could either greatly increase their smuggling operations or put pressure on the royal customs officials to grant the merchants clearance papers. Both methods were widely used.

The great trading center of Boston particularly had to face the port problem. The Assembly had first thought to make unstamped trade legal on the ground that no stamps existed, and guaranteeing to indemnify officers who might be penalized by Britain for such action. But the Assembly shrewdly decided that such a stand would compromise the cause, for it would concede the legality of the Stamp Act if there were a stamp master in the colony. Instead, the Massachusetts Assembly, unwilling to go so far as to encourage open resistance, left the whole matter to the Sons of Liberty, who were quite willing to assume the responsibility.

The first step was to gain time, and this the Boston merchants (as well as the merchants of all the colonies) did by putting every possible ship out to sea before the November 1 deadline. In the meanwhile, the royal officials—the governor, controller, collector of customs, advocate general of the admiralty court, attorney general, and surveyor general of the customs of New England—engaged in a complex farce-comedy of passing the buck in deciding on clearance policy for the port. Cutting through this confusion were the Sons of Liberty, which put intense pressure on the customs collectors and threatened to storm the customhouse with a mob by December 17. Then the radicals showed their power by again forcing a public resignation from stamp master Andrew Oliver. A mob of two thousand such as pressured Oliver could not be ignored, and the customs officials promptly capitulated, agreeing to provide ship clearances without stamps.

Philip Dawe: The_Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering

On the night of December 17, the Sons of Liberty celebrated their highly significant victory, and it was particularly fitting that the brilliant organizer of the radicals, Sam Adams, was feted as the guest of honor.

The earliest—and easiest—resolution of the problem came in Virginia, which had the good fortune of having a liberal and understanding surveyor general in Peter Randolph, of the eminent Virginia family. As early as November 2, Randolph advised all the customs collectors to clear all vessels without stamped paper. Governor Fauquier of Virginia was also intelligent about the issue, and quickly seconded Randolph’s stand. The customs officials in Rhode Island promptly followed. The merchants of Philadelphia used an ingenious device of adding clearances to partially loaded cargo ships before November, to extend their time of grace through that month. Governor John Penn induced the collector to go along with the scheme. By early December, however, the Philadelphia harbor was filled with vessels and the customs officials faced squarely the problem of clearances. Writing to England, the Philadelphia collectors admitted their fear of the populace should they enforce the Stamp Act, and they soon began to issue ship clearances.

In a few days, the Philadelphia breakthrough was enormously widened by Charles Stewart, surveyor general of customs for the Eastern Middle District (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware). Stewart authorized all the customs officials to issue ship clearances without stamps, and again gave the threat of popular force as his justification. New York customs officials were especially relieved; they had suffered the growing pressure of the populace, particularly of the seamen unemployed by the stoppage of trade.

New England’s ports were in effect blasted open by the surrender of the Boston customs officials in mid-December. Duncan Stewart, collector at New London, Connecticut, was forced to give way a few days before Boston; New Haven, Connecticut, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, followed a few days after. There was a little resistance by customs officials at Portsmouth, but this was arrested by a mob demonstration on December 26, and there was no clearance trouble after that.

Except for Virginia, the main customs difficulties were experienced in the South. Maryland did not finally issue clearances without stamps at the main port of Annapolis until the end of January. The courageous Peter Randolph tried his best to open up the Carolinas as he had Virginia, but he was foiled for a long time by the zeal of the governors and local customs officials. In South Carolina, Randolph joined with the Assembly, the merchants, the shipowners, and the rest of the people to battle the stubborn Governor William Bull. Finally, the resigned stamp master Caleb Lloyd reaffirmed his resignation, and began to issue certificates of unavailability of stamps to attach to clearance papers. By mid-February, ships were sailing legally from South Carolina without stamps.

Meanwhile, North Carolina’s reactionary governor, William Tryon, tried a particularly shrewd maneuver in attempting to induce submission to the Stamp Act. While blocking any meeting of the Assembly, Tryon convened a private meeting of fifty leading planters and other gentlemen of the colony, and tried to sell them on abandoning resistance. Assuring them that he personally strongly opposed the Stamp Act, Tryon urged them to submit to the tax and enjoy untrammeled trade, while he personally would appeal to Britain for special favors for North Carolina. As a further inducement, he promised to pay personally for the cost of the stamps required on papers issued by him.

The leading citizens, however, spurned this shrewd appeal to ease and short-run cupidity, and firmly refused the offer. North Carolina suffered from closed ports until February, when the customs officials finally gave in. The one exception was the port of Cape Fear in extreme southern North Carolina. There, a particularly reactionary set of royal officials cracked down rigorously to enforce the Stamp Act. Captain Jacob Lobb of the Royal Navy had had the gall, in early January, to seize several vessels coming into Cape Fear, because their clearance papers officially issued in other American ports were unstamped. When William Dry, collector at Brunswick, North Carolina, proposed to present the confiscated vessels at the Halifax Vice Admiralty Court, a group of citizens from Brunswick, New Hanover, and Bladen Counties gathered at Wilmington on February 18 to form an association to prevent operation of the Stamp Act. The association quickly amassed a thousand men and marched on Brunswick, capturing control of the town and the port. Seizing the recalcitrant William Dry, the association searched for the ships’ papers, and won from Dry and Captain Lobb the release of the three vessels and a promise to open the port from then on. On February 21, the citizens rounded up all the court and customs officials and forced them to swear an oath not to execute the Stamp Act. North Carolina at last was free of Stamp Act tyranny, and the happy citizens sailed back to Wilmington on the liberated ships.

Stamp Act Denounced

Georgia, the southernmost of the rebellious colonies, also had its troubles. Georgia allowed ships to clear without stamps until the end of November, when Governor James Wright and the customs officials closed the ports. Governor Wright persisted in his dictatorial course despite the pleas of merchants and shippers. When George Angus distributed stamped paper during his brief term of office in January, the Savannah merchants earned the hatred and contempt of all other merchants and colonists for selling out to the stamp tax by applying for stamped paper. The rural people throughout Georgia, similarly outraged, gathered in arms six hundred strong on January 27, ready for an angry march on Savannah. For Governor Wright, too, discretion proved to be the better part of valor; on hearing news of the threatened march, Wright hurriedly shipped the papers onto a British vessel, where they were effectively out of circulation. Very shortly Savannah was operating without stamps. Thus, by the end of February, even the most recalcitrant officials in the South were all permitting open ports, while the northern ports had all been opened by the end of 1765.

If the customs officials could be successfully intimidated, what about the British naval officers beyond the reach of colonial harassment—at least while at sea? Generally, the colonists found that the British navy did not much bother to enforce the Stamp Act. Astute entrepreneurs in Philadelphia began to issue insurance policies to shippers against British seizure, at the low rate of two and one-half percent, thus indicating the lax state of enforcement. Moreover, American shippers soon began to find that they could land unmolested without stamped papers at English-run ports that themselves were obeying the stamp rules—including ports in Quebec, Nova Scotia, Florida, the West Indies, and even England itself! During the period of the temporary closing of American ports, illegal smuggling increased greatly, thereby generating further contempt for English authority. Indeed, the customs officials began to issue clearances partly out of fear that they would soon be ignored completely by the colonists. The Philadelphia officials wrote perceptively that “we must now submit to necessity, and do without them [the stamped papers], or else in a little time, people will learn to do without either them or us.

Once in a while, a rigorist naval officer persisted in plaguing the colonists. Captain Archibald Kennedy, for one, insisted on stopping all vessels leaving New York, even after the port was officially opened, and blocking the path of any whose clearance papers were unstamped. Since Kennedy allowed all entering ships to proceed, New York City soon accumulated a large population of discontented, unemployed seamen ready to rebel against the laws of trade.

One reason for the lax naval enforcement, ironically enough, was the forced closing of the admiralty courts for lack of stamps. Only the Halifax court was now open. With these courts closed, the naval officers were reluctant to detain ships for any length of time.

The civil courts were not opened so quickly, but then the need was not nearly as pressing as in the case of the ports. We have seen the positive advantage of the closed admiralty courts as well as the informal substitutes for domestic legal transactions. Moreover, as long as the civil courts remained closed, English merchants could not collect on the substantial sum of debts owed them by Americans. This blockage could only lead British merchants to put pressure on Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. George Washington, Richard Henry Lee, and other Virginia tobacco planters, generally in heavy debt to English merchants, saw the importance of this method of creating pressure. As a result, the pressure to reopen the courts was far less than that to reopen the ports.

Pressure for reopening the courts came mainly from the Sons of Liberty and other radicals who wanted the opening to symbolize judicial repudiation of the Stamp Act. Thus, as soon as the ports were opened in Massachusetts, the Sons of Liberty went to work on the courts. The Massachusetts Council was openly warned:

Open your Courts and let Justice prevail

Open your Offices and let not Trade fail

For if these men in power will not act

We’ll get some that will, in actual Fact.

This popular pressure was succeeded by arguments by leading lawyers of Boston. Young John Adams argued before the Council that the Stamp Act was “utterly void,” for it violated colonial “rights as men and our privileges as Englishmen.” When Parliament errs, declared Adams boldly, it need not be obeyed, and it had no right to impose taxes on the colonies. James Otis, Jr. this time backed the Adams’ view. The Council worriedly passed the buck to the judges of the colony, attempting to wash its hands of the entire problem.

The Massachusetts Superior Court was not scheduled to convene until March, but two lower courts in Suffolk County, containing Boston, were supposed to meet in January. The Probate Court of Suffolk County was being held up by Thomas Hutchinson, judge of the court; Hutchinson was soon told that his only viable alternatives were “to do business without stamps, to quit the country, to resign [the] office, or——.” Keeping the stampless court closed, it was made clear, was not a healthy path for Hutchinson to choose. Faced with this threat, Hutchinson consented to have his more pliable brother, Foster, replace him as judge of the probate court, which promptly opened its doors, followed by the inferior court of the county.

Having secured the opening of their own county courts by mid-January, the Boston radicals put pressure on the Massachusetts Assembly to open the other courts in the province. The House passed a resolution to open all the courts of justice by the overwhelming vote of 81 to 5, but again the Mephistophelian Thomas Hutchinson blocked its passage in the Council. The radical Boston Gazette, spearheaded by Otis, denounced Hutchinson bitterly, but the Council, not wanting to take any positive stand, also blocked the proposal of Governor Bernard to arrest Otis for his seditious essay. Finally, the Council again passed the buck to the judges of the colony, who in turn passed it over to the lawyers to decide. Faced with such responsibility, the lawyers, including Otis, began to stall. After a token hearing of one case in the crucial superior court during March, the court adjourned without taking action, to await passively the now rumored imminent repeal of the Stamp Act.

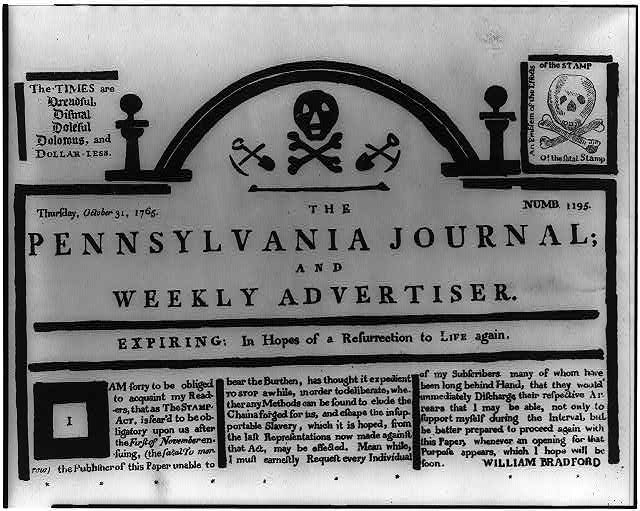

Pennsylvania Journal & Weekly Advertiser on the Stamp Act

Virginia displayed the same vacillation and hesitancy in opening its courts. Edmund Pendleton, a judge in Caroline County, and one of Virginia’s most respected lawyers, urged keeping the courts open on the same hard-hitting grounds as the Boston libertarians. Justice Littleton Eyre of the Northampton County Court took the same stand. But other judges were far less courageous, and they dithered along without taking the decisive step. The Virginia lawyers, tough in talk and in theory, also balked at taking the public step of reopening the courts. As a result, the courts of Virginia, as in Massachusetts, largely remained closed, with the exception of Accomack County. In Accomack, on the eastern shore, the courts defiantly reopened, but few other lower courts joined in.

The story in most of the other colonies was much the same. In colony after colony the lawyers approved the high libertarian principle of keeping open in disregard of an invalid stamp tax, but timorously continued to delay putting their high ideals into practice. The judges likewise continued to stall until the thrilling news of repeal of the Stamp Act reached the colonies in early April, and took them all off the spot. This was conspicuously the case, for example, in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. In New Jersey and Pennsylvania, however, a few lower courts managed to remain open. In New York, an attempt by judges of the court of common pleas to reopen was harshly crushed by a threat of Governor Henry Moore to fire any judges who dared to open without stamps. The courts of South Carolina also dithered throughout the period, but by March justices of the Charleston Court of Common Pleas attempted to reopen. They were responding to pressures by merchants, traders, and their associated Sons of Liberty in Charleston, and backed by the South Carolina Assembly. However, the judges were blocked in this effort by the court clerk Dougal Campbell and by Governor Bull.

Among the colonies, then, only four—New Hampshire, Maryland, Delaware, and Rhode Island—opened all of their courts before the repeal came through. Meeting in early February, the New Hampshire Superior Court overruled the obstructionism of its clerk, and the victory was promptly hailed by the Portsmouth Sons of Liberty. Some of Maryland’s lower courts opened as early as November, but the superior court did not open until forced to do so in early April by repeated demands at a mass meeting at Annapolis of the Sons of Liberty from all over the colony. The courts of Delaware were opened in February under severe pressure from its grand jury, which refused to perform its task of making criminal indictments (which were not subject to the stamp tax) until the civil courts agreed to reopen.

Little Rhode Island was unique among the colonies. There all the courts remained open without interruption. In this colony, the backbones of the judges were fortified by the Assembly’s pledge to indemnify all officials who ignored the Stamp Act, and all the courts continued happily to function. In one case before the superior court, the hated ex—stamp master Augustus Johnston refused to prosecute in his capacity as king’s attorney. The court expressed its contempt for British rule by replacing Johnston as attorney general with Silas Downer, secretary of the Providence Sons of Liberty.

While most of the colonial civil courts, especially the superior courts, remained closed during the Stamp Act era, it is clear that legal and judicial shilly-shallying could not have continued forever. Mounting popular pressure undoubtedly would soon have forced a general reopening of the courts had not repeal intervened. However, it is likely, from their attitude, that the judges would have proceeded timorously on the practical ground that stamps were unavailable rather than have taken a stand on constitutional principle.