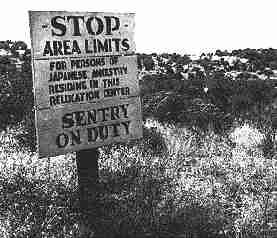

NOTE: Today marks the anniversary of FDR signing executive order 9066, which authorized the “indefinite detention” of nearly 150,000 people on American soil.

NOTE: Today marks the anniversary of FDR signing executive order 9066, which authorized the “indefinite detention” of nearly 150,000 people on American soil.

The order authorized the Secretary of War and the U.S. Army to create military zones “from which any or all persons may be excluded.” The order left who might be excluded to the military’s discretion. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt inked his name to EO9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, it opened the door for the roundup of some 120,000 Japanese-Americans and Japanese citizens living along the west coast of the U.S. and their imprisonment in concentration camps. In addition, between 1,200 and 1,800 people of Japanese descent watched the war from behind barbed wire fences in Hawaii. Of those interned, 62 percent were U.S. citizens. The U.S. government also caged around 11,000 Americans of German ancestry and some 3,000 Italian-Americans.

Today, people around the country say are saying “never again” – and working to resist the same kind of arbitrary power to detain people with no due process written into the 2012 National defense Authorization Act. Washington state Senator Bob Hasegawa is one of those people. Following is the story of his family’s personal experience with indefinite detention, originally published on the Daily Caller website.

For most Americans, the debate over indefinite detention provisions written in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2012 plays out primarily as an academic exercise. The average Joe walking down Main Street U.S.A. simply doesn’t worry about armed government thugs snatching him up, throwing him in the back of a van and hauling him off to some camp somewhere.

But one Washington state senator plunged into the NDAA fray with much more than academic, political or rhetorical interest. For Sen. Bob Hasegawa, indefinite detention without due process is personal.

His family lived it.

Hasegawa’s parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts, along with their entire community, spent three years living in barrack shacks behind barbed wire and armed guards at Minidoka Internment Camp in southern Idaho, not knowing if, or when they would ever get out.

Their crime?

Japanese ancestry.

“While they were constructing the camp, my family lived in horse stalls in the stables at the Puyallup Fairgrounds,” he said. “They were all U.S. citizens.”

The Seattle Democrat was the first member of his family born after internment. The injustice his family endured needs no explanation, but he said the sad legacy of that experience lingers on even today.

“They never talked about it at all,” he said. “It was sort of like a community embarrassment, and they internalized it.”

That shame led to a suppression of Hasegawa’s culture and heritage. His parents rarely spoke Japanese after that. He said they didn’t want the kids to have an accent. They gave their children American soun ding names – like Bob.

ding names – like Bob.

“They didn’t want anything to be held against us, be it race or ethnicity. They wanted to shield us from that.”

Many Americans write off the danger of indefinite detention powers, arguing they “only apply to terrorists.” Hasegawa bristles at such rhetoric.

“It makes me angry – really angry,” he said with barely contained emotion. “So many presidents gave lip service. When President Gerald Ford finally rescinded EO9066 in 1976, he said, ‘I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise – that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.’ Yet, it seems we have to relive these lessons.”

Hasegawa said he often runs into the “it could never happen to me” mentality.

“That makes me think of that German priest’s quote about Nazi Germany. What was his name? He said, ‘There was nobody to speak up for me…’”

The quote Hasegawa references is attributed to Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller.

“First they came for the communists, and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a communist. Then they came for the socialists, and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a trade unionist. Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me.”

With his family’s experience motivating him, Hasegawa decided he needed to step up and speak for any future victims of unjust federal force. On Feb.1, 2013 he filed SB 5511 in the Washington Senate. The bill condemns sections of the NDAA allowing for indefinite detention without due process as unconstitutional and includes provisions blocking any such attempts in the Evergreen State. It forbids any state agency cooperation with federal indefinite detention attempts and provides criminal penalties for anybody who tries.

Republican Rep. Jason Overstreet sponsored similar legislation in 2012 and filed a House companion bill this session. Overstreet reached out to Hasegawa across the political aisle after learning about his family’s internment during a “Day of Remembrance” in the Washington House last year. Hasegawa said he’s happy that they can work together and form a coalition to protect the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

- Writs, Riots, and Redcoats: Hancock’s Spark of the Revolution - January 17, 2026

- The National Bank That Breached the Articles of Confederation - June 2, 2025

- Virginia Association of 1769: A Step Toward Continental Unity - May 12, 2025