What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared we would become a captive audience. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared that we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions.” In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate would ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.—Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

Thus goes the strain of thought in two of the great prophetic minds of literature, not so much opposed in their rationale as intertwined like the serpentine strands of DNA. The relevance of Aldous Huxley and George Orwell lies in their fears, which in recent years are being actualized at an accelerated pace.

Like the automatons of Orwell’s 1984, our glazed eyes have melted into the television screen. Recent statistics, for example, indicate that approximately 1 in 7 or 42 million Americans cannot read a newspaper or even the instructions on a pill bottle.

If people cannot read, or if they simply will not, the safeguard of a democracy—an educated and informed citizenry—is in peril. The importance of an educated citizenry, as envisioned by the architects of the American scheme of government, is that they have the analytical and intellectual wherewithal to recognize and challenge the inevitable corruption of government. Without such an education, inevitably, the people become pawns in the hands of unscrupulous government bureaucrats.

Have we become pawns manipulated by a government-entertainment complex? This was the question debated in seventeen episodes of The Prisoner, the British television series that baffled and confused a generation and still intrigues viewers today.

Regarded by many as the finest dramatic television series ever broadcast, The Prisoner first aired in Great Britain 45 years ago. The subsequent summer of 1968, a summer of dissidence and unrest, sixteen of the seventeen episodes were broadcast in the United States (and reprised in the summer of 1969). The strength of this enigmatic series rode on the heels of Patrick McGoohan, who had built a reputation as the spy John Drake in the Secret Agent television series. After tiring of the Drake role, McGoohan immediately fell headlong into The Prisoner as he wrote, directed and otherwise hovered over the series.

The themes of The Prisoner are still relevant today—the rise of a police state, the freedom of the individual, the perversion of science and the nature of man—and they in part account for the series’ cult following.

“I am not a number. I am a free man,” was the mantra chanted on each episode of The Prisoner. Perhaps the best visual debate ever on individuality and freedom, the story centers around McGoohan, a man who finds himself living in a mysterious, self-contained, cosmopolitan community known as The Village. The Village’s inhabitants are known merely by numbers, and McGoohan is Number 6.

In the opening episode (“The Arrival”), Number 6 meets Number 2, who explains to him that he is in The Village because information stored “inside” his head has made him too valuable “outside.” Number 6 chooses not to give in to Village authorities but struggles to maintain his own identity. “I will not make any deals with you,” he pointedly remarks to Number 2. “I’ve resigned. I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, debriefed or numbered. My life is my own.” Thus, Number 6 remains a prisoner, although his captivity is spent in an idyllic setting with parks and green fields, recreational activities and even a butler.

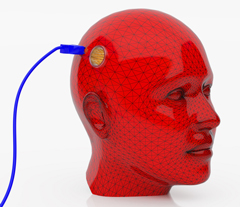

Number 6 seeks to preserve his individuality as a “free man” as he tries to escape from The Village or learn the identity of Number 1, the person presumed to run The Village. But Number 6 is watched continually by surveillance cameras and other devices, and his escapes are thwarted by ominous white balloon-like spheres known as “rovers.” In the final episode (“Fall Out”), Number 6 overcomes his overseers and discovers that he was Number 1 all along.

Although esoteric, The Prisoner was McGoohan’s vehicle for translating some very definite viewpoints to the screen. As he stated in a 1982 interview:

It was about the most evil human being, human essence, and that is ourselves. It is within each of us. That is the most dangerous thing on the Earth, what is within us. So, therefore, that is what I made Number 1—oneself—an image of oneself which he was trying to beat.

The most pernicious element of this evil essence is the domination and annihilation of individuality and freedom, which are essential to human nature. Thus, initially the struggle for freedom is against oneself.

Fundamentally, however, The Prisoner is an epistemological exercise that focuses on the concept of reality, both in the subjective and objective sense—that is, can we really know anything about anything? Is reality a mere social construct? Since society creates any knowledge that people may possess, does this mean that human beings are simply products of the given social setting from which they are manufactured? As Steven Paul Davies notes in The Prisoner Handbook(2002): “Thinking for yourself is not necessarily thinking by yourself.” And as Number 2 warns Number 6 in the episode entitled “Once upon a Time”:

Society is the place where people exist together. That is civilization. The lone wolf belongs to the wilderness. You must not grow up to be a lone wolf.

Therefore, the ultimate goal of those in power is conformity to the constructs of society. This means both figuratively and literally eliminating the lone wolf, the individual. Modern psychiatry defines “normality” as conformity. This “measuring of the human psyche by psychologists,” as Davies puts it, has seriously affected how we live our lives and how we view nonconformists. Media representations of “normality” have become the criteria that society uses to evaluate its members. The concept of normality has become subjective as our views have changed to meet societal demands. The individual, as the term was once defined, is becoming passé. As McGoohan commented in 1968:

At this moment individuals are being drained of their personalities and being brainwashed into slaves. The inquisition of the mind by psychiatrists is far worse than the assault on the body of torturers.

In a media-dominated age in which the lines between entertainment, politics and news reporting are blurred, it is extremely difficult to distinguish fact from fiction. Moreover, the struggle to remain “oneself in a society increasingly obsessed with conformity to mass consumerism,” writes Davies, means that superficiality and image trump truth and the individual. The result is the group mind and the tyranny of mob-think.

Huxley clearly saw that people would come to love entertainment and trivia, and that those would destroy their capacity to think and eventually annihilate any freedom we may possess. Humanity’s bent toward distractions—that is, the bread and circuses of entertainment—leads them to sell their collective souls for one more voyeuristic peek into a celebrity’s life. Indeed, our society is one in which people’s love of entertainment and trivia, according to Davies, has “destroyed their capacity to think and takes away their freedom.”

McGoohan was quoted as saying that “freedom is a myth.” When we think of freedom, what exactly are we talking about? After all, none of us is free to choose when and where we are born, what sex we are, who our parents are and so on. As we reflect on the question of freedom, we see that there is very little freedom at all. We are so bombarded with images, dictates, rules and punishments and stamped with numbers from the day we are born that it is a wonder we ever ponder a concept such as freedom. “We’re all pawns,” notes a character in Episode One, in a game that cruelly plays itself out for most of us. In essence, this means that the only hope for true freedom is to break the chains of destiny in an attempt at some momentary individualistic moment, something few ever experience.

In the end, we are all prisoners of our own mind. In fact, it is in the mind that prisons are created for us. And in the lockdown of political correctness, it becomes extremely difficult to speak or act individually without being ostracized. Thus, so often we are forced to retreat inwardly into our minds, a place without bars from which we cannot escape, and into the world of video games and the Internet. That’s why The Prisoner’s existential experience of continually questioning everything, including ourselves, is so vital to any concept of individuality. It is only within this existential questioning that there is hope for what we may call freedom.

The fact that The Prisoner even attempts to raise such questions is astounding. It is against the meltdown of the modern mind that The Prisoner stands, and it is this background that gives it increasing relevance.

McGoohan’s ambivalence about the concept of freedom is reflected in the surrealism of the final episode. Number 6 emerges from The Village into the center of London. The Village, then, is the present reality. In an earlier episode (“The Chimes of Big Ben”), when Number 6 believes he has escaped to a Secret Service office in London, he asks his superior: “I risked my life … to come back here, home, because I thought it was different … it is, isn’t it? Isn’t it different?”

Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead [send him mail] is founder and president of The Rutherford Institute. He is the author of The Change Manifesto (Sourcebooks).

Copyright © 2012 The Rutherford Institute