An analysis of Judge Katherine Forrest and Hedges v Obama

An analysis of Judge Katherine Forrest and Hedges v Obama

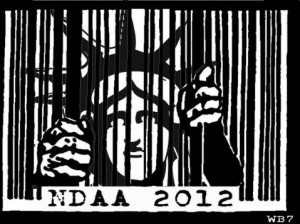

In a historical ruling on Hedges, et al. v Obama, et al. on Wednesday, May 16, Judge Katherine Forrest of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York preliminarily enjoined the Federal Government from enforcing section 1021 of the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

Section 1021 purports to authorize the President to designate all persons — including U.S. Citizens found within the U.S — as enemy combatants, subject to the Law of War, including; Indefinite detention without trial or charge, transfer to foreign jurisdictions or entities (commonly known as extraordinary rendition), and military tribunals. Section 1021 authorizes enemy combatant status not just for “terrorists,” but also for the broad and undefined; those who “substantially support Al-Qaeda, the Taliban or Associated Forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.” Those covered by section 1021 are unclear and subject to abuse because it is not limited to individuals directly responsible for terrorism or belligerent acts; it applies to vague ‘substantial support’ for undefined ‘associated forces.’ Section 1021 leaves these key terms undefined; and up to the President’s discretion. Importantly, section 1021 does not require a mens rea or scienter requirement to one’s substantial support. Thus, someone may be subject to the NDAA without ever knowingly or recklessly providing such substantial support.

Mr. Hedges and his co-plaintiffs — reporters, activists, organizers and even a politician from Iceland critical of the U.S. war on terror — have asserted that section 1021 is vague to such an extent that it provokes fear that certain of their potential associations and expressions, including journalistic, political and organizing activities, could subject them to indefinite or prolonged military detention; violating their First Amendment Free Speech and Fifth Amendment due process rights. Each Plaintiff testified that section 1021 has already had a chilling effect on such associational and expressive activities–and it would continue to do so. Mr. Hedges, for example, is a reporter that has interviewed numerous alleged terrorists and terrorist organizations, and testified he no longer interacts with or reports on many such groups out of fear section 1021 may subject him to military detention.

The Government opposed the plaintiffs’ request for preliminary injunctive relief on three grounds. First, that plaintiffs lack standing because they have not been detained pursuant to the NDAA. Second, that even if the Plaintiffs have standing, they have failed to demonstrate an imminent threat requiring preliminary relief. Finally, the Government argued that Section 1021 of the NDAA is simply an “affirmation” or “reaffirmation” of the authorities already conferred by the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (“AUMF”), and thus, the NDAA does not now suddenly subject the Plaintiff to any new immediate disposition that requires injunctive relief.

On April 16, 2002, The Tenth Amendment Center filed an Amicus Curiae brief in support of the Plaintiffs, alleging that section 1021 of the NDAA is unconstitutionally vague and overbroad because it is does not define who is covered and what conduct is prohibited. The Tenth Amendment Center put forth compelling arguments that those covered by the “substantial support” standard are unclear because that term is undefined and overly broad, and importantly, there is no knowing requirement to such support. Moreover, the NDAA does not define the “associated forces” one may not provide “substantial support” to. This rank vagueness is violative of Fifth Amendment due process rights.

The Tenth Amendment Center also discussed how the NDAA is unconstitutional on its face because it is rooted in the 2001 AUMF, which is itself an unconstitutional congressional delegation of war making authority, and that the NDAA violates Article III section III’s treason clause because it forgoes the constitutional requirements to prove treason. These later arguments were not central to the Courts ultimate decision.

STANDING

As a Preliminary matter, the Court was required to decide whether or not the Plaintiffs possessed standing to contest section 1021 prior to being disposed according to its provisions. Standing is established in this case if a litigant shows a concrete injury in fact, or imminent injury, caused by section 1021, that a preliminary injunction can remedy. Because the Plaintiffs’ have not been formally subject to the NDAA, it is more difficult to establish standing to contest the law. The Plaintiffs took the position that their present cessation of journalistic and political associations and expressions, as well as their well-grounded fear of the imminent application section 1021 due to their past and future activities, establishes the concrete injury sufficient for standing.

The Court’s method of analysis first dispenses with the Government’s contention that the section 1021 is nothing more than an affirmation of the AUMF. The Court found — as advanced by the Tenth Amendment Center and Rhode Island Liberty Coalition for months — the NDAA far exceeds those powers permitted by the 2001 AUMF. This is an important distinction because if section 1021 only reaffirmed the already-existing 2001 AUMF powers of the executive, and the Plaintiffs’ various activities have not so far subjected any of them to those already-existing powers, the Plaintiffs’ argument that section 1021 created imminent peril (the requirement for Court-issued preliminary injunction of a Congressional Act) would be undermined.

Instead, the Court found that the 2001 AUMF was limited to responding to the 9/11 attacks, while section 1021 casts a broad net that potentially encompass numerous of the Plaintiffs’ activities unassociated with 9/11 or those responsible for 9/11. In fact, and of central importance to the Court’s decisions, was that the Government lawyers could not even define what section 1021 “substantial support” encompassed, and they would not aver that the Plaintiffs past, current and potential future journalistic and political expressional and associational activities would not subject them to section 1021.

“I can’t make specific representations as to particular plaintiffs. I can’t give particular people a promise of anything” said the Government Lawyer at hearing.

The Court aptly noted: “It must be said that it would have been a rather simple matter for the Government to have stated that as to these plaintiffs and the conduct as to which they would testify, that Section 1021 did not and would not apply, if indeed it did or would not. That could have eliminated the standing of these plaintiffs and their claims of irreparable harm. Failure to be able to make such a representation given the prior notice of the activities at issue requires this Court to assume that, in fact, the Government takes the position that a wide swath of expressive and associational conduct is in fact encompassed by § 1021.”

The Court further found that the Plaintiffs’ expressive and associational deprivations are actual current, substantial,injuries to the Plaintiffs, and that the Plaintiffs’ also faced future, imminent and particularized invasion of legally-protected interests as potential covered persons under NDAA section 1021. The Court rightly found that these current and imminent harms, coupled with the significant gravity of indefinite detention, enabled the Plaintiffs to contest the NDAA’s constitutionality without first formally being designated as subject to section 1021 by the Government.

Accordingly, the Court found that the Plaintiff’s had standing because each “has shown an actual fear that their expressive and associational activities are covered by § 1021; and each of them has put forward uncontroverted evidence of concrete–non-hypothetical–ways in which the presence of the legislation has already impacted those expressive and associational activities.”

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

In order to demonstrate entitlement to preliminary injunctive relief, the Plaintiffs were required to show (a) a likelihood of success on the merits of their claims of section 1021’s constitutional infirmity; (b) that they will suffer irreparable harm in the absence of the requested relief; (c) that the balance of the equities tips in their favor; and (d) that the injunction is in the public interest. Even in the face of the maxim that the Court must seek to find an interpretation of the statute that upholds the constitutionality of the legislation, section 1021 is so overbroad and vague that the Court was unable to do so.

The first, and most important, analysis concerns section 1021’s constitutionality. The Plaintiffs first assert that Section 1021’s over breadth captures their expressive and associational conduct in violation of their rights under the First Amendment. Separately, the Plaintiffs, and the Tenth Amendment Center in its Amicus Curiae brief, assert that the statute’s profound vagueness violates due process rights under the Fifth Amendment.

The Court was first tasked with determining which type of scrutiny to apply to the NDAA section 1021’s alleged infringement on the First Amendment’s associational and expressive rights; the tepid rational basis test, the heightened scrutiny test, or the strict scrutiny test where the Government must present a compelling justification for its infringement. Strict Scrutiny is an extremely heavy balancing test for the Government to overcome because it involves the infringement of a fundamental Constitutional right; in this case the content-based deprivation of First Amendment political expressive and associational conduct.

The Court justly found that Strict scrutiny applied because “each of the four plaintiffs who testified at the evidentiary hearing put forward evidence that their expressive and associational conduct has been and will continue to be chilled by section 1021. The Government was unable or unwilling to represent that such conduct was not encompassed within section 1021. Plaintiffs have therefore put forward uncontroverted proof of infringement on their First Amendment rights.”

Applying the strict scrutiny test, the Court remarked on long-established case law holding that only the “exceptional circumstances” of political speech that incites violence, is obscene, or is incidental to criminal activity, may be prohibited. The Plaintiffs past and potential future political conduct, which the Court concluded is encompassed by Section 1021, simply does not rise to those levels prohibited political speech. Accordingly, the Court concluded that section 1021 is unconstitutional as a violation of the First Amendment.

The Second prong of Constitutional analysis concerns the Plaintiffs’, and the Tenth Amendment Center’s, contention that NDAA section 1021 is unconstitutional as a violation of the FifthAmendment’s Due Process Protections. To satisfy the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, individuals are entitled to understand the scope and nature of statutes which might subject them to criminal penalties. Although the NDAA concerns military law, the punishment is criminal in nature, and the Court accordingly applied the criminal statute test: A penal statute must define the criminal offense (1) with sufficient definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited and (2) in a manner that does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement. That analysis is performed against the backdrop of a strong presumption of validity given to acts of Congress.

The Court then remarked on an interesting facet of Constitutional examination: a Due Process analysis usually is “as applied” — meaning that the facts of those allegedly deprived of due process drive the consideration, or put otherwise; ‘did this person’s treatment violate due process.’ Except however, where the statute does not contain a “mens rea” or scienter requirement, e.g. a requirement that one knowingly or recklessly committed the prohibited conduct. As argued by the Tenth Amendment Center, the Court found that section 1021 does not have a mens rea or scienter requirement; that one may still even be subject to section 1021 even though they had no knowledge their conduct “substantially supported” a terrorist organization. The Court found that in these circumstances, Constitutional challenges based on due process may be asserted based on the plain language of the statute, without regard to the underlying facts of the complaining litigant.

Moving on to its analysis, the Court remarked: “Before anyone should be subjected to the possibility of indefinite military detention, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment requires that individuals be able to understand what conduct might cause him or her to run afoul of § 1021. Unfortunately, there are a number of terms that are sufficiently vague that no ordinary citizen can reliably define such conduct.” The Court refers specifically to section 1021’s prohibition of providing vague “substantial support” for Al-Qaeda, the Taliban or undefined “associated forces.”

The Court noted that although “associated forces” may be subject to definition (“individuals who, in analogous circumstances in a traditional international armed conflict between the armed forces of opposing governments, would be detainable under principles of co-belligerency”), not even the Government was able to define precisely what “direct” or “substantial” “support” means. And of course, the Government was unable to state that plaintiffs’ conduct fell outside section 1021. In addition, the Government even conceded that the statute lacks a scienter or mens rea requirement of any kind. Thus, an individual could run the risk of substantially supporting or directly supporting an associated force without even being aware that he or she was doing so.

The Court stated that “the vagueness of § 1021 does not allow the average citizen, or even the Government itself, to understand with the type of definiteness to which our citizens are entitled, or what conduct comes within its scope” and emphatically concluded that “In the face of what could be indeterminate military detention, due process requires more.” Furthermore, the Court ruled that the section 1021 is so overbroad and unspecific that the Court is not able to construe it in a limiting manner to comport with the Constitution. To do so, the Court would have to rewrite the law to such a great extent that it would unconstitutionally adopt the Legislative function; this is strictly prohibited.

Finding that the section 1021 expands that which was authorized by the 2001 AUMF and is an unconstitutional deprivation of First and Fifth Amendment guarantees, and because the Government could not say whether the Plaintiffs’ conduct subjects them to section 1021, the Court then easily concluded that the potential of the Plaintiffs’ indefinite detention constituted imminent and irreparable harm.

The Court finally recognized the strong public interest in citizen retention of First and Fifth Amendment rights, and determined that these fundamental rights balanced the equities between the parties in favor of the Plaintiffs. The Plaintiffs risk of indefinite detention far outweighed the Government’s proffered powers under section 1021. Indeed, the Court noted that if an injunction issued, the Government would still possess all the war powers of the 2001 AUMF, just not the expansive and unconstitutional ones contained within section 1021.

The Court then granted the Plaintiff’s motion for preliminary injunction halting enforcement of section 1021 of the NDAA pending further order of the Court or amendments to the statute rendering its Opinion & Order moot.

One extremely interesting wrinkle is that Plaintiffs Kai Wargalla, of the UK, and Brigitta Jonsdottir, of Iceland, are not U.S. citizens, and for the most part, do not live in the U.S. Yet the Court did not distinguish between these individuals’ and the citizen-Plaintiffs’ Constitutional rights. The Court also did not forbid the application of section 1021 to only the U.S. homeland. Thus, the Court’s decision can be interpreted as applying to citizens and non-citizens alike, potentially located anywhere.

Striking!

The path the Government takes is unclear. There likely will be an appeal to a higher Court where most of these questions will again be dealt with. However, on appeal, the Court’s findings that the section 1021 does apply to the Plaintiffs will likely be preserved, and will form the factual basis for appeal. The system works, for now!

- A Response to Senator Lee on Indefinite Detention - December 2, 2012

- The Feinstein Fumble: Indefinite Detention Remains - November 30, 2012

- Judicial Juggling: NDAA vs. Fundamental Rights - October 4, 2012