NDAA section 1022(a)(1)-(2) requires the president to detain members of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and individuals directly responsible for belligerent actions against the United States. Section 1022(b) specifically excludes U.S. citizens, and legal aliens for actions occurring within the United States.

NDAA section 1022(a)(1)-(2) requires the president to detain members of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and individuals directly responsible for belligerent actions against the United States. Section 1022(b) specifically excludes U.S. citizens, and legal aliens for actions occurring within the United States.

Section 1021(b)(2) authorizes the President to designate persons as enemy combatants that “substantially supported” Al-Qaeda, the Taliban or “associated forces engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.” Section 1021 is subject to abuse because it applies to vague “substantial support” for undefined “associated forces.”

Moreover, although section 1021(d) states it is not intended to limit or expand the scope of the 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF), section 1021(b)(2)’s covered persons extend beyond the parameters of the AUMF (which was limited to those responsible for 9/11 and those who harbor them).

Did Congress and the President really expand an authorization to use military force with a multi-hundred page appropriation bill? So much for a Constitutionally-required declaration of war…

Pursuant to section 1021(c), the president may dispose of such covered persons according to the Law of War, including: 1) Indefinite detention without charge or trial, 2) Military tribunals, and 3) transfer to foreign jurisdictions or entities.

Section 1021 does not exclude U.S. citizens and legal aliens for actions occurring within the United States as section 1022(b) does. In fact, the U.S. Senate rejected an amendment by Senator Udall that would have banned the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens. Section 1021(e) merely seeks to preserve existing law and authorities pertaining to the detention of U.S. citizens, legal resident aliens, and all other persons found within the United States.

The law and authorities concerning the President’s authority to designate U.S. citizens as enemy combatants are unclear. The WWII case of Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942) authorized the president to designate as enemy combatants German saboteurs found within the U.S. In Hamden v. Rumsfeldi, 542 U.S. 507 (2004) the Supreme Court ruled that a U.S. citizen found on a foreign battlefield may be designated an enemy combatant, but is entitled to a measure of due process: at least a military hearing to determine his status as an enemy combatant (where hearsay may come in and the burden may be on the alleged enemy combatant).

The recent Fourth Circuit case of Padilla v. Hanft, 423 F.3d 386 (4th Cir. S.C. 2005) permits enemy combatant status for U.S. citizens captured within the U.S. whose actions are encompassed by the 2001 AUMF. The Supreme Court refused to review the legality of Padilla’s military detention upon Padilla’s transfer to civilian jurisdiction on the eve of Supreme Court review, with three justices sharply dissenting. Padilla v. Hanft, 547 U.S. 1062 (2006). The dissenting judges in Padilla felt strongly that the indefinite detention in Padilla was a harm capable of repetition and the case should be dealt with by the Court. Indeed, if the Supreme Court had not entertained the Bush administration’s jurisdictional hop scotch and ruled on the authority of the President to designate U.S. citizens captured in the U.S. as enemy combatants, we would have clarity on the President’s powers.

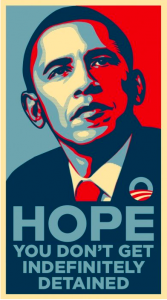

There should be no grey areas concerning our fundamental rights to liberty and due process. It ought to be clear whether U.S. citizens found within the United States may be designated as enemy combatants. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has not offered concrete guidance on this question and has enabled the grey area the NDAA regrettably seeks to exploit. In fact, the office of President, under Bush and Obama, has asserted the ability to designate persons captured within the U.S., including U.S. citizens, as enemy combatants subject to the Law of War. Certainly, clarity from the Supreme Court is called for.

If U.S. citizens (and others) within U.S. may be designated as enemy combatants, numerous Constitutional rights and protections afforded defendants in normal criminal proceedings and trials for treason would not be present. In Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008), our Supreme Court held that persons designated as enemy combatants for indefinite detention possess the right to a military hearing to contest their confinement, and may seek a writ of habeas corpus from the civilian courts. However, hearsay evidence is freely admissible and a preponderance of the evidence standard is sufficient for continued detention until the cessation of hostilities (although the question of whether a lesser standard of proof would be sufficient for indefinite detention has been left open). See Al-Bihani v. Obama, 590 F.3d 866 (D.C. Cir. 2010); Al Odah v. United States, 611 F.3d 8 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

Think about that: you may be indefinitely detained based on hearsay that proves you were more likely than not an enemy combatant. No proof beyond a reasonable doubt or even clear and convincing evidence is needed to indefinitely keep you incarcerated. Such “enemy combatants” do not have the right to a jury of peers, whether for continued indefinite detention or ultimately, at a military tribunal. These military proceedings deny our most fundamental rights enshrined in the 4th 5th 6th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution, subvert civilian authority to the military, and strike at the very heart of who we are as Americans. Section 1021’s authorization to transfer persons to foreign jurisdictions, outside the reach of our Courts, is perhaps the most disconcerting. The fundamental rights possessed by a U.S. citizen, or other person, captured in the U.S. and transferred to a foreign jurisdiction, are entirely unclear.

Although President Obama signed the NDAA, he issued a signing statement expressing serious reservations: “I have signed this bill despite having serious reservations with certain provisions that regulate the detention, interrogation, and prosecution of suspected terrorists. . . . I want to clarify that my Administration will not authorize the indefinite military detention without trial of American citizens. Indeed, I believe that doing so would break with our most important traditions and values as a Nation.” However, neither President Obama, nor his successor, are bound by this signing statement. And Obama mentions nothing about military tribunals or transfer to foreign jurisdictions of persons found within the U.S..

One must certainly question the President’s judgment: why would he sign the NDAA if he was cognizant of the grave implications to the Constitutional rights of persons within the U.S.? There is probably nothing more deserving of a Presidential veto than the NDAA! Given that Senator Carl Levin admitted on the floor of the Senate that the President demanded section 1021 apply to U.S. citizens, Obama’s signing statement is nothing more than politician double-speak. While every American should feel insulted by such underhanded political gamesmanship, the members of the armed forces have the double-affront of also being funded by a bill that purports to shred the very Constitution they have sworn their lives to protect.

- A Response to Senator Lee on Indefinite Detention - December 2, 2012

- The Feinstein Fumble: Indefinite Detention Remains - November 30, 2012

- Judicial Juggling: NDAA vs. Fundamental Rights - October 4, 2012