by Steve Palmer, Pennsylvania Tenth Amendment Center

by Steve Palmer, Pennsylvania Tenth Amendment Center

One thing I have noticed during my fifteen months working with the Tenth Amendment Center is that when people use the words, “nullification” and “interposition”, they don’t always seem to mean the same things. Even articles by people who agree about these concepts give subtle, contextual clues that we aren’t necessarily thinking of the same ideas when we use these words. On the surface, it’s simple. “Nullification” is when a state declares a law null, void and invalid.  “Interposition” is when a state inserts itself between the federal government and the state’s citizens on behalf of the citizens. Surprisingly, though, when you think a little more carefully about it, things start getting muddled pretty quickly. For example, are “nullification” and “interposition” two words for the same thing? If not, do they overlap? Which branch of government does them?

Matt Spalding, with The Heritage Foundation gives us a great example of this confusion. In his article, rejecting the concept of nullification, he writes,

The important distinction between Madison’s idea of interposition and Calhoun’s theory of nullification should be kept clear and bright, and has practical application in today’s debates.

And

A different approach can be seen in the Firearm Freedom Acts passed in 8 states (proposed in 22 more) cleverly designed to challenge expansive federal claims of regulatory authority under the Commerce Clause. South Carolina is doing the same with the Incandescent Light Bulb Freedom Act. These acts are aggressive state actions that challenge federal laws—but they are not nullification. Nor is it nullification when states refuse to participate in federal programs and mandates, such as the REAL ID Act. (emphasis added)

From these excerpts, it becomes clear that not only do Mr. Spalding and I disagree about the proper role for nullification in the states, but worse, we don’t even agree about what “nullification” means.  To me, when a state refuses to participate in a federal mandate, such as the REAL ID Act, that is just about as close as possible to the textbook meaning of “nullification” as you can get.

We’re never going to be able to agree about the proper role for nullification if we can’t even agree on what it means. Apparently, Mr. Spalding is on board with all these legislative examples he lists, but rejects some nebulous concept known as “Calhoun’s theory of nullification”. While it would also be useful to address some of the other points in Mr. Spalding’s article, that will have to wait for another day. The point of this article is simply to propose a way of organizing the concepts of nullification and interposition so that when we discuss them, we are at least thinking of the same ideas.

Proposing a Framework

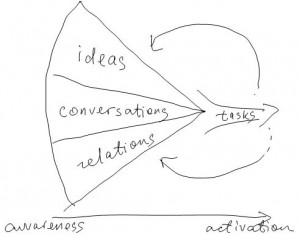

To this end, I decided to try to draw a diagram to organize my own thoughs on these concepts. It turned out to be more difficult than I thought, but here is what I came up with (so far).

Describing the Diagram

In this diagram, nullification is a subset of interposition. That is, “nullification” is “interposition”, but “interposition” is not necessarily “nullification”. “Nullification” and “interposition” themselves are not seen as specific actions, but rather as categories into which actions fit. The various ovals in the diagram are color-coded to represent the “strength” of the measure and positioned within the lines to reflect the branch of state government which can execute them. The royal blue ovals represent forms of interposition which are not nullification. The turquoise ovals are passive forms of nullification where the state declares a federal action invalid, but doesn’t actively resist federal efforts at enforcement or implementation. The red ovals are the confrontational forms of nullification where the state says that a federal action is invalid and the state will prevent the federal government from enforcing or implementing its program.

It should be noted that all of these actions can, theoretically, be applied before or after a Supreme Court ruling. The position of the Tenth Amendment Center is that the state has the final authority to interpret the Constitution for itself.  Unfortunately, that opinion is not yet held by everyone.   Before a Supreme Court ruling, however, none of the actions in this diagram should be controversial.

Interposition

In this model, I included three forms of interposition: 1.) Resolutions by the state legislature, 2.) litigation by the state’s executive branch and 3.) nullification by one or more branches of the state government.

Examples of legislative resolutions include the Tenth Amendment Resolutions which have passed or are presently under consideration in many states. Another example is Pennsylvania’s 1811 Resolution Against the Bank. An example of interposition in the form of litigation by the executive branch comes to us in the form of the lawsuits by 28 states, including Pennsylvania, against the patient protection and affordable care act. I do not consider these state actions to be nullification because neither one effects the functioning of the federal law which it targets. Instead, both depend upon further action by another branch or level of government in order to restore the Constitution.  The “stay” and “injunction” by the judicial branch also come to mind as possible forms of interposition, but I couldn’t think of any specific examples off the top of my head, so I did not include them.

Nullification

And that brings us to nullification.  In this framework, “nullification” can be performed individually by any of the branches of state government or by multiple branches in conjunction.

Executive Branch

One form of nullification comes when the executive branch refuses, without prompting by the state legislature, to implement or enforce a federal program. Examples can be seen in the states of Florida and Alaska, both of whom have announced their refusal to implement the Patient Protection and Affordable Care act. Even the Supreme Court agrees that the executive branch of the state may refuse to enforce or implement a federal program, writing in the case of Mack/Printz v. USA,

We held in New York that Congress cannot compel the States to enact or enforce a federal regulatory program. Today we hold that Congress cannot circumvent that prohibition by conscripting the State’s officers directly. The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems, nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivision, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program. It matters not whether policymaking is involved, and no case by case weighing of the burdens or benefits is necessary; such commands are fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system of dual sovereignty.

In other words, the federal government cannot require any state official to enforce or implement a federal program. End of discussion. Sheriff DeMeo took nullification into the “red zone” by actively preventing the federal bureau of land management from enforcing their program. It is interesting to note that Nye County, NV joined Sheriff DeMeo, interposing by passing a resolution. While this article focuses on nullification and interposition by the state, it happens at other levels too.

Judicial Branch

A state’s judicial branch can nullify a federal law by simply declaring it unconstitutional. This was done, for example, in the instance of Joshua Glover, when the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared the Federal Fugitive Slave Act to be unconstitutional.

Legislative Branch and Collaboration

When the legislative branch passes a law which is in conflict with a federal law, that branch of government is acting to nullify the federal law. There are numerous examples of this form of nullification, including state medical marijuana laws, Real ID non-compliance measures and firearm freedom acts. Legislative measures of this sort are more effective when they are also supported by the actions of the executive branch and the decisions of the courts. As we see in California, where LAPD and LA County Sheriff department members joined federal officials on a recent raid of a medical marijuana dispensary, the other branches of state government do not always collaborate.

Pennsylvania’s Personal Freedom Law, which made it kidnapping when a bounty hunter attempted to return an escaped slave to his state of origin, was an example of a legislative measure which had escalated into the red zone of our diagram. Proposed TSA limiting laws in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Texas which consider unconstitutional “strip searches” and “aggressive pat downs” to be assault are modern examples.

Conclusion

While it may not be important that everyone adopts this particular framework when talking about nullification and interposition, it is tremendously important that we know what framework is being used when we talk to each other about these concepts. When confronted with someone who opposes the concepts of nullification and interposition, before arguing about the validity and proper uses for nullification, perhaps the starting point should be to seek common ground on the definitions of the words. It may turn out that by agreeing on what the words mean, we may find that we have more in common than we knew. Also, organizing the instances of nullification and interposition using a framework like this may illuminate some tactical understandings that aren’t as easily discerned through verbal descriptions.

Steve Palmer [send him email] is the State Chapter Coordinator for the Pennsylvania Tenth Amendment Center.