In response to a recent article here at the Tenth Amendment Center, a reader raised the issue of nullification and its ties to bigotry. Specifically, the reader wondered how the fact that some states tried to nullify orders to desegregate government schools should be addressed. The question was asked if states can “use nullification for any reason they want – even if it’s a bad reason?” With charges of racism being the go-to ad hominem, these are important questions. Therefore, solid, well argued responses are necessary to combat the efforts of opponents to stain the principle of nullification.

In response to a recent article here at the Tenth Amendment Center, a reader raised the issue of nullification and its ties to bigotry. Specifically, the reader wondered how the fact that some states tried to nullify orders to desegregate government schools should be addressed. The question was asked if states can “use nullification for any reason they want – even if it’s a bad reason?” With charges of racism being the go-to ad hominem, these are important questions. Therefore, solid, well argued responses are necessary to combat the efforts of opponents to stain the principle of nullification.

The short answer is no, states can’t use nullification for any reason. At least that doesn’t seem to be the way it was meant to be employed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, when they drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Nullification was meant to be used in the event the federal government usurped the power retained by the states, e.g., any authority not delegated under the constitution. But this question also alludes to issues related to a federal system, in particular, what happens if a state passes a law that restricts someone’s freedom? How might a society deal with, say, one state prohibiting abortion under any circumstance and a neighboring state allowing abortion no questions asked? I’ll address these issues and attempt to answer some of these sorts of questions. Note however that in no way is this definitive, and suggestions are welcome.

First, it is critical to understand the big picture here, namely that nullification involves pitting one government against another. The fact that states are smaller and less able to persecute minorities in no way detracts from the desire by those who control them to use what power they do have, most often for evil purposes. Because of this, one shouldn’t assume that states won’t be tempted to exercise unjust authority. It’s not as if we’re dealing with a clear-cut good vs. evil match; at best we’re setting two evils against one another, and rooting for the underdog.

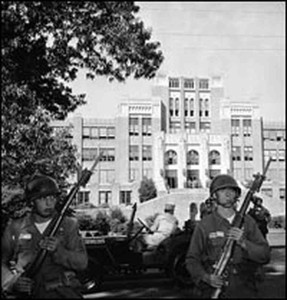

The other aspect of this, at least in regards to Arkansas trying to nullify desegregation, is the nature of the federal system. In brief, the states created the federal government, delegated several powers to it, and retained all authority not explicitly listed in the compact, the constitution. The states also reserved the power to interpret the constitution, and to reject legislation not deemed to be pursuant to that document’s original intent.

At least one way to look at the racial segregation in Arkansas was that state’s agents didn’t believe the federal government had been granted any authority over the issue and weren’t going to be told how to run their schools. In no way should this be taken as an endorsement of segregation, but it could shed some light on the situation. Nor is this the only possible explanation of the Arkansas government’s decision. It’s entirely possible that the state’s institutions were dominated by racial bigots determined to repress minorities at any opportunity. Again, this goes to the heart of the problem, which is government power.

The very nature of a decentralized government system is one that is diverse, organic, and more easily adapted when change becomes necessary. Given this, we should expect to see a wide array of policy decisions being made that in one way or another reflect the values and cultural norms of the states or even regions. It’s reasonable to assume that schools in different parts of the country will adopt varying curricula, and emphasize subjects that are more tailored to their region. It’s possible that in some conservative states evolution will be taught secondary to creationism; in more liberal states the opposite may be true, or creationism may be ignored entirely.

Other controversial issues, such as abortion, drugs, gay marriage, labor laws, and welfare could also be starkly different from one state to another. The more liberal states might tolerate abortion and some drug use, while both are strictly prohibited in the neighboring “red” states. The result of these state-level policy decisions will generally be that like-minded people eventually congregate, and provided people mind their own business, conflict will be largely avoided. I’ve noted before that most controversy takes place when differing factions vie for control over one polity; reducing the scope of power of as many levels of government will aid in preventing this. Another advantage of this system is that when power is more localized, it is easier to escape into neighboring communities that are perhaps more friendly to personal liberty. Being forced out of one town or state by laws one views as tyrannical is certainly unpleasant, but it’s almost certainly more feasible than having to emigrate internationally. It should also be noted that one possibility is for states to remain neutral on an issue, and defer instead to local governments.

I recognize the reality of the situation, and don’t hold onto any delusions that government bureaucrats and politicians will just cede control. I realize that such thinking is mostly theoretical and much is left to be done before we can look forward to such an organization of society. I further understand that it’s in the nature of governments to grow, to expand their power and never to give up any control voluntarily. So there is no guarantee that any lasting peace and freedom would come from just reducing federal and state power without a total rollback. But there is no harm in imagining what a free society might look like; or at least one that is freer than currently exists.

This theorizing and imagination is part of what goes into explaining how nullification works, how decentralized government power is a thing to welcome, rather than fear. Most people, I would venture to guess, are clueless as to how such a federal system might operate. After all, the voluntary union has been dead for almost a hundred and fifty years, and virtually no one is still living who remembers a time when there was a federal system as outlined in the constitution.

Those inclined to liberty are frequently accused of being utopians, dreamers, or living in a fantasy land by people who support the idea of giving all the guns and all the power to a small group of technocrats and politicians, and then expecting everything to turn out all right. If that’s not ironic, the word means nothing.

So yes, nullification has certainly been put to use by institutions that had malicious intentions and wanted to use it to control others. In no way however should this dissuade individuals from supporting it for the purpose of liberating people. Rejecting something like nullification out of hand because our betters tell us it’s not okay is self-defeating. The fact that an idea is not endorsed by the “ghetto of academia,” as Mike Maharrey refers to the cadre of political correctness, is all the more reason to support it.

To be sure, nullification isn’t a panacea; it won’t solve the underlying problem, which is government power. Nullification is merely a tool that can be used to push back, to buy some time and create some space for freedom to grow. Ultimately, there has to be a fundamental change in the minds of enough people regarding the moral legitimacy and efficacy of government, before anyone can hope to rollback the state.

- Some Clarification on ‘Integrity’ - August 14, 2013

- Copperhead: A Tenther Film Review - July 19, 2013

- Edward Snowden: Nullifier - June 25, 2013