The Judicial juggling of our most fundamental rights of liberty and due process – in this case, to not be kidnapped and imprisoned indefinitely with no trial or charge pursuant to the NDAA — continues. And, unfortunately, as with pretty much all review of Legislative and Executive actions, the judiciary continues to presume those actions valid; even now, when the soul of our constitutional republic is at stake.

The Judicial juggling of our most fundamental rights of liberty and due process – in this case, to not be kidnapped and imprisoned indefinitely with no trial or charge pursuant to the NDAA — continues. And, unfortunately, as with pretty much all review of Legislative and Executive actions, the judiciary continues to presume those actions valid; even now, when the soul of our constitutional republic is at stake.

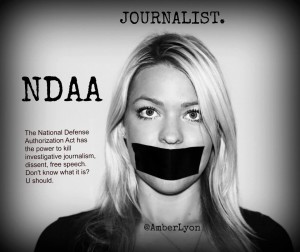

Many groups and organizations have stood up against the NDAA. TAC has been leading – with much success – state and local nullification throughout the Country (http://tenthamendmentcenter.com/nullification/ndaa/). A group of activists and reporters, led by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Christopher Hedges, opted to work within the Federal judicial system and sued president Obama in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

TAC communication director Mike Maharrey has provided a great summation of events as of September 18, 2012 (http://blog.tenthamendmentcenter.com/2012/09/judge-reinstates-federal-kidnapping-powers/). Briefly, Judge Katherine Forrest of the District Court permanently enjoined the President from utilizing NDAA section 1021. In an incredibly reasoned and brave decision, she found that NDAA section 1021 is unconstitutional because it has actually and unreasonably infringed on the 1st Amendment expressive and journalistic activities of the Plaintiffs. Moreover, the NDAA section 1021 is void on its face as a violation of the 5th Amendment’s Due Process clause because section 1021 is effectively a criminal statute with no mens rea requirement (“knowing” “willful” “recklessly”, etc…) where one cannot determine what conduct is prohibited (The NDAA broadly outlaws the undefined “substantial support” of terrorist groups or “associated forces”).

Judge Forrest also aptly noted the limited process those detained under NDAA section 1021 would have; a right to administrative hearing without a jury, where hearsay is admissible (there is no 6th Amendment right to face accusers) and the standard for indefinite detention is the much-lower-than-beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard of “clear and convincing evidence.” Any judicial review in a habeas corpus proceeding conducts an analysis with this same limited Constitutional protections, pro-Executive, review.

Upon Judge Forrest’s Order enjoining the use of NDAA section 1021, Obama Administration lawyers immediately petitioned both Judge Forrest and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals for a temporary stay of the Order. Judge Forrest declined, but the Second Circuit’s duty judge, Raymond Lohier, issued a temporary stay of the order pending further decision by the Second Circuit.

Well, today, a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit has extended the temporary stay of Judge Forrest’s order pending final resolution of the case in the Second Circuit. The three-judge panel, all Obama appointees, found that the “public interest” weighed in favor of extending the stay. Interestingly, a deeper look into the Second Circuit’s decision reveals deeply flawed logic and ends based reasoning that certainly does not protect the “public interest.” Such Judicial analysis, even without stating so, errs on the side of finding Congressional acts Constitutional, even where our most fundamental rights are undermined.

1) The Second Circuit first states that ‘The government avers that the Plaintiffs – journalists and activists – were in no danger of detention and detainment by theU.S.military.’

Au contraire! At trial before Judge Forrest the government could not state what activities were covered by NDAA section 1021, or whether the Plaintiffs’ activities would subject them to indefinite detention. Furthermore, and most important, Judge Forrest ruled – and she was right on with this one – that the application of section 1021 to the plaintiffs was irrelevant in a Due Process analysis. Normally, one must have standing (an injury in fact) under a statute in order to contest that statute’s validity. The exception to this standing requirement is where, as with NDAA section 1021, the statute is criminal in nature, there is no mens rea requirement, and the prohibited conduct is not defined. Such a statute is unconstitutional on its face and may be challenged without first being brought under its provisions. The vague, broad and undefined NDAA section 1021 clearly falls into this category, enabling the Plaintiffs the ability to contest section 1021 without demonstrating an injury in fact.

2) The Second Circuit next states ‘That the NDAA on its face does not affect existing laws and authorities concerning U.S.citizens and those arrested within the United States.’

TAC has written extensively about the emptiness of this NDAA section 1021 purported preservation provision (http://tenthamendmentcenter.com/2012/03/02/a-brief-legal-and-mildly-political-analysis-of-the-ndaa/). We must remember that the Senate specifically rejected an amendment that would have banned the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens, and instead inserted this vague preservation phrase. This legislative history strongly indicates Congress intended to provide the president war powers to the fullest extent possible under existing law and authorities, including the ability to indefinitely detain.

Yet, unfortunately, the laws and authorities on this subject are unclear, and actually indicate that U.S.citizens and others captured within the United Statesmay be designated as enemy combatants subject to indefinite detention. In the WWII case of ex parte Quirin our Supreme Court held that German saboteurs captured within the United States, including a U.S. Citizen, could be designated enemy combatants. Perhaps most illustrative of the NDAA preservation provision’s limited protections is that the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals — the highest post 9/11 Court to consider the question – actually ruled in the Padilla case that a U.S. citizen captured within the U.S may be designated a enemy combatant.

Essentially, NDAA section 1021 legislatively authorizes to the fullest extent possible the President’s professed war power to indefinitely detain those in the U.S., which the Fourth Circuit has already blessed. There are simply no laws or authorities (other than the plain language of the Constitution!) that reasonably protect those in the U.S. from section 1021 indefinite detention kidnapping, and the Second Circuit should not hang its reasoning on such empty words.

3) Finally, the Second Circuit states ‘That Judge Forrest’s ruling appears to go beyond the NDAA to limit the 2001 AUMF (“Authorization to Use Military Force”).’

The Second Circuit’s final professed basis to stay Judge Forrest’s Order is troubling as well. Judge Forrest specifically distinguished the language of NDAA from the 2001 AUMF, and demonstrated how the NDAA vastly exceeds those war powers in 2001 AUMF. In short, the 2001 AUMF authorized action against those who planned, or supported those who planned, the 9/11 attacks. More broadly, and vague, NDAA section 1021 applies to the undefined “substantial support” of terrorist and associated forces. section 1021 extends far beyond those responsible for 9/11 to now cover these undefined persons and actions. The persons and actions encompassed by the NDAA’s provisions are so broad and undefined that Judge Forrest determined the NDAA violates our 5th Amendment Due Process rights; not even the government at trial could define what actions or persons were subject to section 1021 of NDAA. While on the other hand, the 2001 AUMF is specific enough to likely survive a Due Process attack because those persons and actions subject to the 2001 AUMF are defined with some degree of certainty. Importantly, Judge Forrest specifically ruled that the president still retained all the powers under the 2001 AUMF, but not those in NDAA section 1021 that vastly exceed the 2001 AUMF.

The Second Circuit used the three above arguments to essentially conclude that it is in the “Public Interest” for the President to retain NDAA section 1021 kidnapping powers, while the citizens’ fundamental constitutional rights continue to be subject to the whims of the President. Such calculation smacks of Orwellian double-speak.

Judge Napolitano recently derided a judicial cannon that presumes acts of Congress valid. Judge Napolitano argued that because the Federal Government is one of limited powers, the judicial cannon should be to presume Congressional acts invalid. Nowhere is Judge Napolitano’s judicial philosophy more apt than to the Second Circuit’s decision to stay Judge Forrest’s Order. With all due respect to the Second Circuit, but the “Public Interest” is best served by erring on the side of caution and protection of citizen rights instead of Executive war powers! That our judiciary presumes Congressional acts valid where those acts directly affect our fundamental Constitutional rights should be of great concern to the cause of liberty and Constitutional governance.

Of particular note going forward is that the Plaintiffs have stated that they will ask the Supreme Court to immediately vacate the Second Circuit’s temporary stay of Judge Forrest’s order. Justice Ginsberg is the duty judge to review Second Circuit decisions, which provides some hope. Justice Ginsberg has been critical of the President’s war powers since 9/11.

Most notably, Justice Ginsberg issued a biting dissent from the Supreme Court’s refusal to review the Fourth Circuit’s decision in the Padilla case that ruled U.S. citizens captured within the U.S. may be designated as enemy combatants and indefinitely detained under the 2001 AUMF. Rarely do judges dissent from decisions declining judicial review. Justice Ginsberg’s dissent in Padilla indicates she may side with the Constitution on this one.

We citizens must continue to work all angles against the NDAA kidnapping powers. While some may continue to seek redress in the Judiciary, we here at TAC will continue to assert what Thomas Jefferson called the “Rightful Remedy,” and nullify this anti-Constitutional aberration at the State and Local levels.

- A Response to Senator Lee on Indefinite Detention - December 2, 2012

- The Feinstein Fumble: Indefinite Detention Remains - November 30, 2012

- Judicial Juggling: NDAA vs. Fundamental Rights - October 4, 2012